|

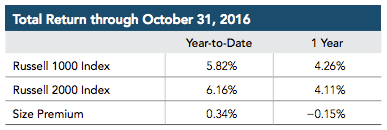

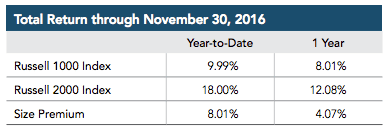

By Weston Wellington Vice President, Dimensional Fund Advisors In the days immediately following the recent US presidential election, US small company stocks experienced higher returns than US large company stocks. This example helps illustrate how the dimensions of expected returns can appear quickly, unpredictably, and with large magnitude. Average returns for US small company stocks historically have been higher than the average returns for US large company stocks. But those returns include long periods of both strong and weak relative performance. Investors may attempt to enhance returns by increasing their exposure to small company stocks at what appear to be the most opportune times. Yet this effort to time the size premium can be frustrating because the most rewarding results often occur in an unpredictable manner. A recent paper1 by Wei Dai, PhD, explores the challenges of attempting to time the size, value, and profitability premiums.2 Here we will keep the discussion to a simpler example. As of October 31, 2016, small company stocks had outpaced large company stocks for the year-to-date by 0.34 percentage points. To the surprise of many market observers, the broad stock market rose following the US presidential election on November 8, with small company stocks outperforming the market as a whole. In the eight trading days following the US presidential election, the small cap premium, as measured by the return difference between the Russell 2000 and Russell 1000, was 7.8 percentage points. This helped small company stocks pull ahead of large company stocks year-to-date, as of November 30, by approximately 8 percentage points and for a full one-year period by approximately 4 percentage points. This recent example highlights the importance of staying disciplined. The premiums associated with the size, value, and profitability dimensions of expected returns may show up quickly and with large magnitude. There is no guarantee that the size premium will be positive over any period, but investors put the odds of achieving augmented returns in their favor by maintaining constant exposure to the dimensions of higher expected returns. The size premium is determined by calculating the difference between the Russell 2000 Index, which represents small company stocks, and the Russell 1000 Index, which represents large company stocks. Frank Russell Company is the source and owner of the trademarks, service marks, and copyrights related to the Russell Indexes. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Indices are not available for direct investment; therefore, their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio.

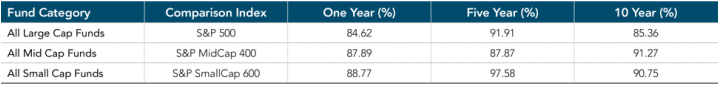

1. Wei Dai, “Premium Timing with Valuation Ratios” (white paper, Dimensional Fund Advisors, September 2016). 2. Size premium: the return difference between small capitalization stocks and large capitalization stocks. Value premium: the return difference between stocks with low relative prices (value) and stocks with high relative prices (growth). Profitability premium: The return difference between stocks of companies with high profitability over those with low profitability. Past performance is no guarantee of future investment results. There is no guarantee an investing strategy will be successful. Small cap securities are subject to greater volatility than those in other asset categories. All expressions of opinion are subject to change. This article is distributed for informational purposes, and it is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any particular security, products, or services. Dimensional Fund Advisors LP is an investment advisor registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission. The close of each calendar year brings with it the holidays as well as a chance to look forward to the year ahead. In the coming weeks, investors are likely to be bombarded with predictions about what the future, and specifically the next year, may hold for their portfolios. These outlooks are typically accompanied by recommended investment strategies and actions that are aimed at trying to avoid the next crisis or missing out on the next “great” opportunity. When faced with recommendations of this sort, it would be wise to remember that investors are better served by sticking with a long-term plan rather than changing course in reaction to predictions and short-term calls. Predictions and Portfolios One doesn’t typically see a forecast that says: “Capital markets are expected to continue to function normally,” or “It’s unclear how unknown future events will impact prices.” Predictions about future price movements come in all shapes and sizes, but most of them tempt the investor into playing a game of outguessing the market. Examples of predictions like this might include: “We don’t like energy stocks in 2017,” or “We expect the interest rate environment to remain challenging in the coming year.” Bold predictions may pique interest, but their usefulness in application to an investment plan is less clear. Steve Forbes, the publisher of Forbes Magazine, once remarked, “You make more money selling advice than following it. It’s one of the things we count on in the magazine business—along with the short memory of our readers.”[1] Definitive recommendations attempting to identify value not currently reflected in market prices may provide investors with a sense of confidence about the future, but how accurate do these predictions have to be in order to be useful? Consider a simple example where an investor hears a prediction that equities are currently priced “too high,” and now is a better time to hold cash. If we say that the prediction has a 50% chance of being accurate (equities underperform cash over some period of time), does that mean the investor has a 50% chance of being better off? What is crucial to remember is that any market-timing decision is actually two decisions. If the investor decides to change their allocation, selling equities in this case, they have decided to get out of the market, but they also must determine when to get back in. If we assign a 50% probability of the investor getting each decision right, that would give them a one-in-four chance of being better off overall. We can increase the chances of the investor being right to 70% for each decision, and the odds of them being better off are still shy of 50%. Still no better than a coin flip. You can apply this same logic to decisions within asset classes, such as whether to currently be invested in stocks only in your home market vs. those abroad. The lesson here is that the only guarantee for investors making market-timing decisions is that they will incur additional transactions costs due to frequent buying and selling. The track record of professional money managers attempting to profit from mispricing also suggests that making frequent investment changes based on market calls may be more harmful than helpful. Exhibit 1, which shows S&P’s SPIVA Scorecard from midyear 2016, highlights how managers have fared against a comparative S&P benchmark. The results illustrate that the majority of managers have underperformed over both short and longer horizons. Exhibit 1. Percentage of US Equity Funds That Underperformed a Benchmark Source: SPIVA US Scorecard, “Percentage of US Equity Funds Outperformed by Benchmarks.” Data as of June 30, 2016. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Indices are not available for direct investment; therefore, their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio. The S&P data is provided by Standard & Poor’s Index Services Group. Rather than relying on forecasts that attempt to outguess market prices, investors can instead rely on the power of the market as an effective information processing machine to help structure their investment portfolios. Financial markets involve the interaction of millions of willing buyers and sellers. The prices they set provide positive expected returns every day. While realized returns may end up being different than expected returns, any such difference is unknown and unpredictable in advance. Over a long-term horizon, the case for trusting in markets and for discipline in being able to stay invested is clear. Exhibit 2 shows the growth of a US dollar invested in the equity markets from 1970 through 2015 and highlights a sample of several bearish headlines over the same period. Had one reacted negatively to these headlines, they would have potentially missed out on substantial growth over the coming decades. Exhibit 2. Markets Have Rewarded Discipline Growth of a dollar—MSCI World Index (net dividends), 1970–2015 In US dollars. Indices are not available for direct investment. Their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. MSCI data © MSCI 2016, all rights reserved. Conclusion As the end of the year approaches, it is natural to reflect on what has gone well this year and what one may want to improve upon next year. Within the context of an investment plan, it is important to remember that investors are likely better served by trusting the plan they have put in place and focusing on what they can control, such as diversifying broadly, minimizing taxes, and reducing costs and turnover. Those who make changes to a long-term investment strategy based on short-term noise and predictions may be disappointed by the outcome. In the end, the only certain prediction about markets is that the future will remain full of uncertainty. History has shown us, however, that through this uncertainty, markets have rewarded long-term investors who are able to stay the course. Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors LP. Diversification does not eliminate the risk of market loss. Investment risks include loss of principal and fluctuating value. There is no guarantee an investing strategy will be successful. All expressions of opinion are subject to change. This article is distributed for informational purposes, and it is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any particular security, products, or services. 1. Excerpt from presentation at the Anderson School of Management, University of California, Los Angeles, April 15, 2003.

|

By Tim Baker, CFP®Advice and investment design should rely on long term, proven evidence. This column is dedicated to helping investors across the country, from all walks of life to understand the benefits of disciplined investing and the importance of planning. Archives

December 2023

|

|

Phone: 860-837-0303

|

Message: [email protected]

|

|

WINDSOR

360 Bloomfield Ave 3rd Floor Windsor, CT 06095 |

WEST HARTFORD

15 N Main St #100 West Hartford, CT 06107 |

SHELTON

One Reservoir Corporate Centre 4 Research Dr - Suite 402 Shelton, CT 06484 |

ROCKY HILL

175 Capital Boulevard 4th Floor Rocky Hill, CT 06067 |

Home I Who We Are I How We Invest I Portfolios I Financial Planning I Financial Tools I Wealth Management I Retirement Plan Services I Blog I Contact I FAQ I Log In I Privacy Policy I Regulatory & Disclosures

© 2024 WealthShape. All rights reserved.