|

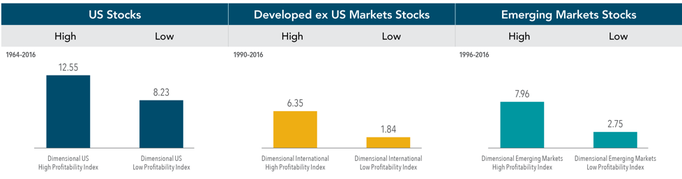

This post comes from our friends at Dimensional. It takes an in-depth look at the profitability factor and the cutting edge empirical research we live by. Be advised: It's a bit heavy on investment terminology. However, it does contain a glossary. Since the 1950s, there have been numerous breakthroughs in the field of financial economics that have benefited both society and investors. One early example, resulting from research in the 1950s, is the insight that diversification can increase an investor’s wealth. Another example, resulting from research in the 1960s, is that market prices contain up-to-the-minute, relevant information about an investment’s expected return and risk. This means that market prices provide our best estimate of a security’s value. Seeking to outguess market prices and identify over- and undervalued securities is not a reliable way to improve returns. This long history of innovation in research continues into the present day. As academics and market participants seek to better understand security markets, insights from their research can enable investors to better pursue their investment goals. In this article, we will focus on a series of recent breakthroughs into the relation between a firm’s profitability and its stock returns. As we will see, an important insight Dimensional drew from this research is how profitability and market prices can be used to increase the expected returns of a stock portfolio without having to attempt to outguess market prices. DIFFERENCES IN EXPECTED RETURNS The price of a stock depends on a number of variables. For example, one variable is what a company owns minus what it owes (also called book value of equity). Expected profits, and the discount rate investors apply to these profits, are others. This discount rate is the expected return investors demand for holding the stock. The impact of market participants trading stocks is that market prices quickly find an equilibrium point where the expected return of a stock is commensurate with what investors demand. Decades of theoretical and empirical research have shown that not all stocks have the same expected return. Stated simply, investors demand higher returns to hold some stocks and lower returns to hold others. Given this information, is there a systematic way to identify those differences? OBSERVING THE UNOBSERVABLE: CURRENT AND FUTURE PROFITABILITY Market prices and expected future profits contain information about expected returns. While we can readily observe market prices as stocks are traded (think about a ticker tape scrolling across a television screen), we cannot observe market expectations for future profits or future profitability, which is profits divided by book value. So how can we use an unobserved variable to tell us about expected returns? A paper by Professors Eugene Fama and Kenneth French published in 2006[1] tackles this problem. Fama and French have authored more than 160 papers. They both rank within the top 10 most-cited fellows of the American Finance Association[2] and in 2013, Fama received a Nobel Prize in Economics Science for his work on securities markets. Fama and French explored which financial data that is observable today contain information about expected future profitability. They found that a firm’s current profitability contains information about its profitability many years hence. What insights did Dimensional glean from this? Current profitability contains information about aggregate investor’s expectations of future profitability. MEASURING PROFITABILITY The next academic breakthrough on profitability research was done by Professor Robert Novy-Marx, a world-renowned expert on empirical asset pricing. Building on the work of Fama and French, he explored the relation of different measures of current profitability to stock returns. Profits equal revenues minus expenses. One particularly important insight Dimensional took from Novy-Marx’s work is that not all current revenues and expenses have information about future profits. For example, firms sometimes call a revenue or expense “extraordinary” when they do not expect it to recur in the future. If those revenues or expenses are not expected to recur, should investors expect them to contain information about future profitability? Probably not. This is what Novy-Marx found when conducting his research. In a paper published in 2013,[3] he used US data since the 1960s and a measure of current profitability that excluded some non-recurring costs so that it could be a better estimate for expected future profitability. In doing so, he was able to document a strong relation between current profitability and future stock returns. That is, firms with higher profitability tended to have higher returns than those with low profitability. This is referred to as a profitability premium. Around the same time, the Research team at Dimensional was also conducting research into profitability. They extended the work of Fama and French and found that in developed and emerging markets globally, current profitability has information about future profitability and that firms with higher profitability have had higher returns than those with low profitability. They also found that this observation held true when using different ways of measuring current profitability. These robustness checks are important to show that the profitability premiums observed in the original studies were not just due to chance. Their research indicated that when using current profitability to increase the expected returns of a real-world strategy, it is important to have a thoughtful measure of profitability that provides a complete picture of a firm’s expenses while excluding revenues and expenses that may be unusual and therefore not expected to persist in the future. THE CUTTING EDGE: NEW RESEARCH Many papers documenting profitability premiums globally have been written since 2013. An exciting forthcoming paper[4] by Professor Sunil Wahal provides powerful out-of-sample US evidence of profitability premiums. Wahal is an expert in market microstructure (how stocks trade) and empirical asset pricing. Fama, French, and Novy-Marx’s research on profitability used US data from 1963 on. Why? Because when they conducted their research, reliable machine-readable accounting statement data required to compute profitability for US stocks was only available from 1963 on. Hand-collecting and cleaning accounting statement data and then transcribing it in a reliable fashion is no easy task and presents many a challenge for any researcher. Wahal rose to those challenges. He gathered a team of research assistants to hand-collect accounting statement data from Moody’s Manuals from 1940 to 1963. By applying his (and his team’s) expertise in accounting, combined with a great deal of meticulous data checking, Wahal was able to produce reliable profitability data for all US stocks from 1940 to 1963. Using this data to measure the return differences between stocks with high vs. low profitability, Wahal found similar differences in returns to what had been found in the post-1963 period. This research provides compelling evidence of the profitability premium pre-1963 and is a powerful out-of-sample test that strengthens the results found in earlier work. THE SIZE OF THE PROFITABILITY PREMIUM So how large has the profitability premium been historically? Large enough that investors who want to increase expected returns in a systematic way should take note. Exhibit 1 shows empirical evidence of the profitability premium in the US and globally. In the US, between 1964 and 2016, the Dimensional US High Profitability Index and the Dimensional US Low Profitability Index had annualized compound returns of 12.55% and 8.23%, respectively. The difference between these figures, 4.32%, is a measure of the realized profitability premium in the US over the corresponding time period. The non-US developed market realized profitability premium was 4.51% between 1990 and 2016. In emerging markets, the realized profitability premium was 5.21% between 1996 and 2016. Exhibit 1. The Profitability Premium Profitability is measured as operating income before depreciation and amortization minus interest expense scaled by book. Indices are not available for direct investment. Their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Index returns are not representative of actual portfolios and do not reflect costs and fees associated with an actual investment. Actual returns may be lower. See “Index Descriptions” in the appendix for descriptions of Dimensional and Fama/French index data. Eugene Fama and Ken French are members of the Board of Directors for and provide consulting services to Dimensional Fund Advisors LP. CONCLUSION In summary, there are differences in expected returns across stocks. Variables that tell us what an investor has to pay (market prices) and what they expect to receive (book equity and future profits) contain information about those expected returns. All else equal, the lower the price relative to book value and the higher the expected profitability, the higher the expected return. What Dimensional has learned from its own work and the work of Professors Fama, French, Novy-Marx, and Wahal, as well as others, is that current profitability has information about expected profitability. This information can be used in tandem with variables like market capitalization or price-to-book ratios to extract the differences in expected returns embedded in market prices. As such, it allows investors to increase the expected return potential of their portfolio without trying to outguess market prices. GLOSSARY Book Value of Equity: The value of stockholder’s equity as reported on a company’s balance sheet. Discount Rate: Also known as the “required rate of return” this is the expected return investors demand for holding a stock. Out-of-sample: A time period not included or directly examined in the data series used in a statistical analysis. Market Microstructure: The examination of how markets function in a fine level of detail, this can include areas of inquiry such as: how traders interact, how security orders are placed and cleared and how information is relayed and priced. Empirical Asset Pricing: A field of study that uses theory and data to understand how assets are priced. Profitability Premium: The return difference between stocks of companies with high profitability over those with low profitability. Realized Profitability Premium: The realized, or actual, return difference in a given time period between stocks of companies with high profitability over those with low profitability. Index descriptions Dimensional US Low Profitability Index was created by Dimensional in January 2014 and represents an index consisting of US companies. It is compiled by Dimensional. Dimensional sorts stocks into three profitability groups from high to low. Each group represents one-third of the market capitalization. Similarly, stocks are sorted into three relative price groups. The intersections of the three profitability groups and the three relative price groups yield nine subgroups formed on profitability and relative price. The index represents the average return of the three low-profitability subgroups. It is rebalanced twice per year. Profitability is measured as operating income before depreciation and amortization minus interest expense scaled by book. Source: CRSP and Compustat. Dimensional US High Profitability Index was created by Dimensional in January 2014 and represents an index consisting of US companies. It is compiled by Dimensional. Dimensional sorts stocks into three profitability groups from high to low. Each group represents one-third of the market capitalization. Similarly, stocks are sorted into three relative price groups. The intersections of the three profitability groups and the three relative price groups yield nine subgroups formed on profitability and relative price. The index represents the average return of the three high-profitability subgroups. It is rebalanced twice per year. Profitability is measured as operating income before depreciation and amortization minus interest expense scaled by book. Source: CRSP and Compustat. Dimensional International Low Profitability Index was created by Dimensional in January 2013 and represents an index consisting of non-US developed companies. It is compiled by Dimensional. Dimensional sorts stocks into three profitability groups from high to low. Each group represents one-third of the market capitalization of each eligible country. Similarly, stocks are sorted into three relative price groups. The intersections of the three profitability groups and the three relative price groups yield nine subgroups formed on profitability and relative price. The index represents the average return of the three low-profitability subgroups. The index is rebalanced twice per year. Profitability is measured as operating income before depreciation and amortization minus interest expense scaled by book. Source: Bloomberg. Dimensional International High Profitability Index was created by Dimensional in January 2013 and represents an index consisting of non-US developed companies. It is compiled by Dimensional. Dimensional sorts stocks into three profitability groups from high to low. Each group represents one-third of the market capitalization of each eligible country. Similarly, stocks are sorted into three relative price groups. The intersections of the three profitability groups and the three relative price groups yield nine subgroups formed on profitability and relative price. The index represents the average return of the three high-profitability subgroups. The index is rebalanced twice per year. Profitability is measured as operating income before depreciation and amortization minus interest expense scaled by book. Source: Bloomberg. Dimensional Emerging Markets Low Profitability Index was created by Dimensional in April 2013 and represents an index consisting of emerging markets companies and is compiled by Dimensional. Dimensional sorts stocks into three profitability groups from high to low. Each group represents one-third of the market capitalization of each eligible country. Similarly, stocks are sorted into three relative price groups. The intersections of the three profitability groups and the three relative price groups yield nine subgroups formed on profitability and relative price. The index represents the average return of the three low-profitability subgroups. The index is rebalanced twice per year. Profitability is measured as operating income before depreciation and amortization minus interest expense scaled by book. Source: Bloomberg. Dimensional Emerging Markets High Profitability Index was created by Dimensional in April 2013 and represents an index consisting of emerging markets companies and is compiled by Dimensional. Dimensional sorts stocks into three profitability groups from high to low. Each group represents one-third of the market capitalization of each eligible country. Similarly, stocks are sorted into three relative price groups. The intersections of the three profitability groups and the three relative price groups yield nine subgroups formed on profitability and relative price. The index represents the average return of the three high-profitability subgroups. The index is rebalanced twice per year. Profitability is measured as operating income before depreciation and amortization minus interest expense scaled by book. Source: Bloomberg. Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors LP.There is no guarantee investment strategies will be successful. Diversification does not eliminate the risk of market loss. All expressions of opinion are subject to change. This article is distributed for informational purposes, and it is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any particular security, products, or services.

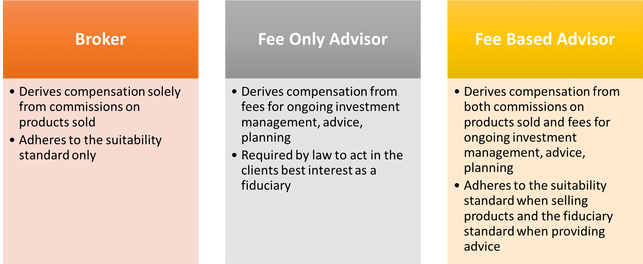

Eugene Fama is a member of the Board of Directors for and provides consulting services to Dimensional Fund Advisors LP. He is a professor of finance at the University of Chicago, Booth School of Business. In 2013, he received a Nobel Prize for his work on securities markets. Ken French is a member of the Board of Directors for and provides consulting services to Dimensional Fund Advisors LP. He is a professor of finance at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth College. Robert Novy-Marx provides consulting services to Dimensional Fund Advisors LP. He is a professor of finance at the University of Rochester, Simon Business School. Sunil Wahal provides consulting services to Dimensional Fund Advisors LP. He is a professor of finance at Arizona State University, Carey School of Business. [1]. Eugene Fama and Kenneth French, “Profitability, Investment, and Average Returns,” Journal of Financial Economics, vol. 82 (2006), 491–518. [2]. G. William Schwert and Renè Stulz, “Gene Fama’s Impact: A Quantitative Analysis,” (working paper, Simon Business School, 2014, No. FR 14-17). [3]. Robert Novy-Marx, “The Other Side of Value: The Gross Profitability Premium,” Journal of Financial Economics, vol. 108 (2013), 1–28. [4]. Sunil Wahal, “The Profitability and Investment Premium: Pre-1963 Evidence,” (December 29, 2016). Available at SSRN: ssrn.com/abstract=2891491. Most professions have a measuring stick to quantify a reputation or skill set. Medical degrees, law degrees and teaching certificates represent recognizable benchmarks for their professions. Our proud service men and women use a chain of command that instantly indicates their level of responsibility. So why is it so difficult to determine whether or not a financial advisor is worth their salt? The term “Financial Advisor” may very well be one of the most misrepresented professional titles. Reason being: Almost anyone can call themselves one. Don’t get me wrong, the financial services industry puts numerous exams and stipulations in place to license and track advisors, but just like any standardized test a passing score isn’t necessarily a great barometer for quality. According to WalletHub there are over 250 thousand advisors across the country. Thankfully, there are ways to help you to determine the background, experience and type of advisors out there. Professional designations such as the CFP® (Certified Financial Planner), CFA (Chartered Financial Analyst®) and the already recognizable CPA, (Certified Public Accountant) give consumers a basic understanding of the training someone has endured. In any vetting process, educational background combined with a professional designation is one of the first things to look for. It’s not to say the absence of one is bad. I know many advisors who do a good job for their clients and don’t have letters after their name, which brings me to my next point. Experience. Type can often be more valuable than tenure. While it’s comforting to see lots of years in the industry, that experience may not add up to a whole lot of knowledge. Here’s a shocker: Some financial services organizations allocate more resources to sales training than education. A good way to decipher experience from fluff is to interview. Just like any job interview, pointed open-ended questions help to uncover details. What types of clients have you worked with? What is your investment philosophy and why? Situational questions such as, “tell me about the message you were sending to your clients back in 2008 and 2009 during the financial downturn,” provide a window into what the experience and expectations could look like. Background. Finance is one of the most regulated industries on the planet largely because it involves money management. A background check is a great way to examine an advisor’s experience, licensing and whether or not any complaints have been filed against them. FINRA (Financial Industry Regulatory Authority) provides a great reference tool. Hint: It will also help you to recognize the different types in the next topic. The Landscape of Financial Professionals There’s a difference between suitability and fiduciary. Similar to the Hippocratic oath to do no harm that a licensed physician takes, a fiduciary is bound by law to act in your best interest. Believe it or not, this isn’t a requirement for most financial advisors. Reason being; if they sell commissionable products, the only obligation is to make sure that the product is suitable for the investor. The phraseology here is interesting. If you were to ask an investor which they would prefer: something that was in their best interest or something that was merely suitable for them, you would likely receive resounding support for the former. Consider the idea of a doctor being solely compensated based upon the treatments or medicines they recommended. The conflict of interest would instantly be apparent. Entering into an engagement with an advisor, whose compensation was based upon the commission from a product sale, isn’t a heck of a lot different from this scenario. The incentives often work in the opposite direction of what's in your best interest, even if they're trying to do the right thing. As fiduciaries, Fee-Only Registered Investment Advisors receive zero commissions because the only product they have to sell is their expertise, something that is quantifiable and transparent, as opposed to sales commissions which are often wrapped into the complexities of a financial products expenses. It’s important to point out the dilemma that Fee-Based Advisors face. Namely, when is it appropriate to sell products to a client based on a standard or suitability, and when is it appropriate to provide advice as a fiduciary acting in their best interest? Many see this as a contradiction. Why wouldn’t someone want to act in my best interest all the time? It’s the critical question that should be asked of every financial professional. Hopefully this sheds some light on a confusing topic. A word of advice would be to know what type of advisor you are speaking with before you even interact with them. Due diligence up front is key because in a business populated by a litany of salespeople, judgment can sometimes get cloudy after a face to face meeting. Financial professionals are always being mischaracterized partly due to an industry that intentionally blurs the lines. Most true Fee-Only Financial Advisors loathe being inadvertently called Brokers, and Brokers often do little to clarify that they aren’t actually acting in a fiduciary capacity. I’m not sure if we’ll ever get away from blanket terminology, but I am sure that individual investors are better served when they’re empowered with the knowledge to make informed choices. *Photo Courtesy of CFP®Board

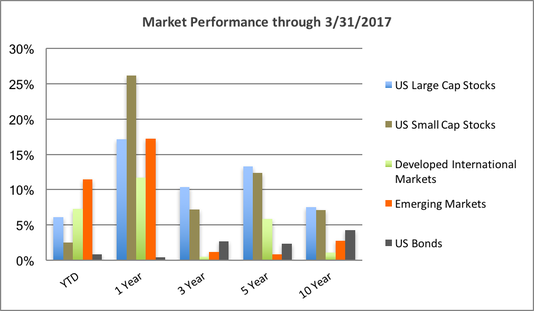

Three months into 2017 markets continued to build on the rally that began shortly after last November’s election. US large companies as measured by the S&P 500 gained 6%, developed foreign markets advanced nearly 7% and emerging markets led the way with over 11% for the quarter. US bonds were relatively flat despite the Fed following through on their promise to incrementally raise interest rates. March 9th marked the 8-year anniversary of the current bull market. It’s not the longest on record (1987-2000), nor is it the shortest. From the 1990’s up until today the S&P 500 has gone from a long bull market to a momentary bear, back to a 5-year bull, leading up to the most recent bear market of ‘08 and finally arriving at today’s bull market. That’s five changes in total, spanning the course of over 26 years. The unpredictable nature of capital markets isn’t news to long term investors, making the significance of the 8-year anniversary essentially a moot point.

Although republicans hold majorities in the house and senate, healthcare reform came and went prior to having a vote. It is yet to be seen when the topic will be revisited as tax reform appears more likely to be the next priority. If anything is predictable in Washington, it’s party gridlock. Until further details unfold, maintaining the status quo is still the best option as opposed to speculating on what may or may not happen. |

By Tim Baker, CFP®Advice and investment design should rely on long term, proven evidence. This column is dedicated to helping investors across the country, from all walks of life to understand the benefits of disciplined investing and the importance of planning. Archives

December 2023

|

|

Phone: 860-837-0303

|

Message: [email protected]

|

|

WINDSOR

360 Bloomfield Ave 3rd Floor Windsor, CT 06095 |

WEST HARTFORD

15 N Main St #100 West Hartford, CT 06107 |

SHELTON

One Reservoir Corporate Centre 4 Research Dr - Suite 402 Shelton, CT 06484 |

ROCKY HILL

175 Capital Boulevard 4th Floor Rocky Hill, CT 06067 |

Home I Who We Are I How We Invest I Portfolios I Financial Planning I Financial Tools I Wealth Management I Retirement Plan Services I Blog I Contact I FAQ I Log In I Privacy Policy I Regulatory & Disclosures

© 2024 WealthShape. All rights reserved.