|

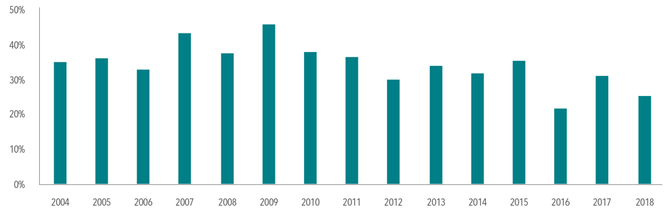

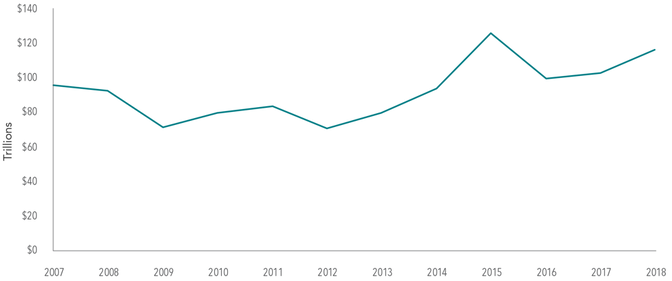

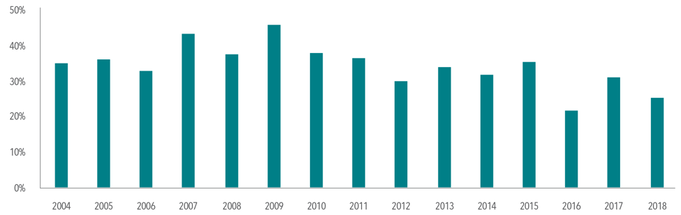

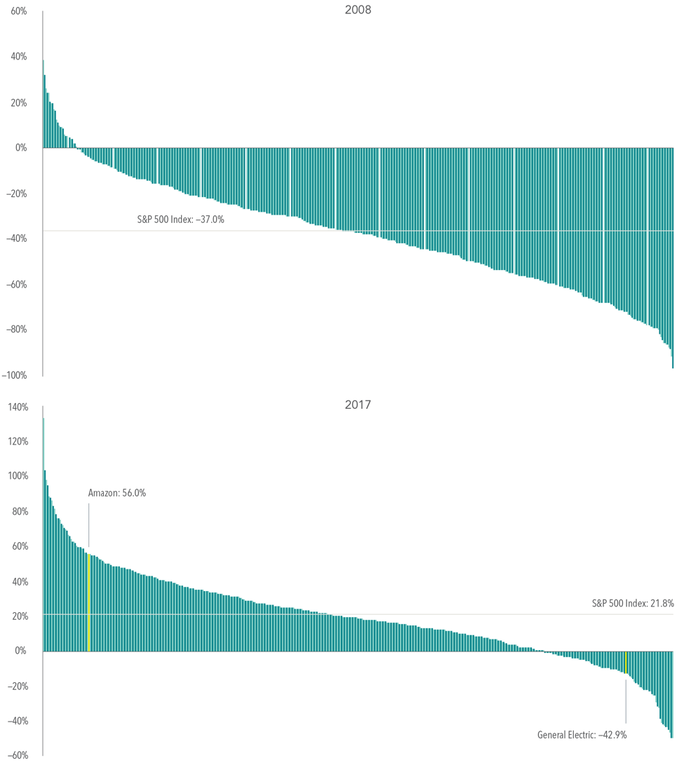

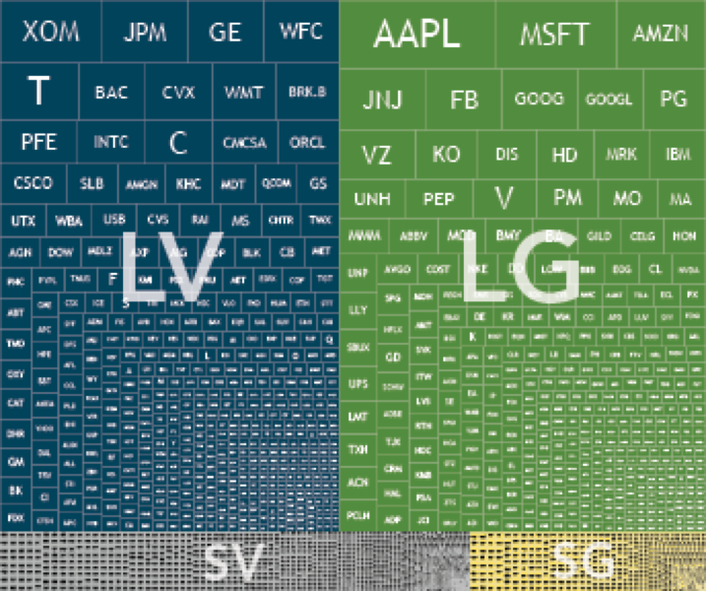

Over the last several years, index funds have received increased attention from investors and the financial media. Some have even made claims that the increased usage of index funds may be distorting market prices. For many, this argument hinges on the premise that indexing reduces the efficacy of price discovery. If index funds are becoming increasingly popular and investors are “blindly” buying an index’s underlying holdings, sufficient price discovery may not be happening in the market. But should the rise of index funds be a cause of concern for investors? Using data and reasoning, we can examine this assertion and help investors understand that markets continue to work, and investors can still rely on market prices despite the increased prevalence of indexing. Many buyers and sellers While the popularity of indexing has been increasing over time, index fund investors still make up a relatively small percentage of overall investors. For example, data from the Investment Company Institute shows that as of December 2017, 35% of total net assets in US mutual funds and ETFs were held by index funds, compared to 15% in December of 2007. Nevertheless, the majority of total fund assets (65%) were still managed by active mutual funds in 2017. As a percentage of total market value, index-based mutual funds and ETFs also remain relatively small. As shown in Exhibit 1, domestic index mutual funds and ETFs comprised only 13% of total US stock market capitalization in 2017. Exhibit 1. Investor Breakdown in the US Stock Market as a Percentage of Total US Stock Market Capitalization All totals may not equal 100% due to rounding. Sourced from the 2018 ICI Fact Book: ici.org/pdf/2018_factbook.pdf In this context, it should also be noted that many investors use nominally passive vehicles, such as ETFs, to engage in traditionally active trading. For example, while both a value index ETF and growth index ETF may be classified as index investments, investors may actively trade between these funds based on short-term expectations, needs, circumstances, or for other reasons. In fact, several index ETFs regularly rank among the most actively traded securities in the market. Beyond mutual funds, there are many other participants in financial markets, including individual security buyers and sellers, such as actively managed pension funds, hedge funds, and insurance companies, just to name a few. Security prices reflect the viewpoints of all these investors, not just the population of mutual funds. As Professors Eugene Fama and Kenneth French point out in their blog post titled “Q&A: What if Everybody Indexed?”, the impact of an increase in indexed assets also depends to some extent on which market participants switch to indexing: “If misinformed and uninformed active investors (who make prices less efficient) turn passive, the efficiency of prices improves. If some informed active investors turn passive, prices tend to become less efficient. But the effect can be small if there is sufficient competition among remaining informed active investors. The answer also depends on the costs of uncovering and evaluating relevant knowable information. If the costs are low, then not much active investing is needed to get efficient prices.” What’s the volume? Trade volume data are another place to look for evidence of well-functioning markets. Exhibit 2 shows that despite the increased prevalence of index funds, annual equity market trading volumes have remained at similar levels over the past 10 years. This indicates that markets continue to facilitate price discovery at a large scale. Exhibit 2. Annual Global Equity Market Trading Volume, 2007–2018 In US dollars. Source: Dimensional, using data from Bloomberg LP. Includes primary and secondary exchange trading volume globally for equities. ETFs and funds are excluded. Besides secondary market trading, there are also other paths to price discovery through which new information can get incorporated into market prices. For example, companies themselves can impact prices by issuing stock and repurchasing shares. In 2018 alone, there were 1,633 initial public offerings, 3,492 seasoned equity offerings, and 4,148 buybacks around the world.3 The derivatives markets also help incorporate new information into market prices as the prices of those financial instruments are linked to the prices of underlying equities and bonds. On an average day in 2018, market participants traded over 1.5 million options contracts and $225 billion worth of equity futures. Hypothesis in practice Even though the historical empirical evidence suggests that the rise of indexing is unlikely to distort market prices, let’s consider the counterargument that the rise of indexing does distort markets and in turn causes prices to become less reliable. In this scenario, wouldn’t one expect stock-picking managers attempting to capture mispricing to have an increased rate of success over time? Exhibit 3 shows little evidence that this has been the case. This chart shows the percentage of active managers that survive and beat their benchmarks over rolling three-year periods. These data show that there is no strong evidence of a link between the percentage of equity mutual fund assets in index funds and the percentage of active funds outperforming benchmark indices. Exhibit 3. Active Manager Performance Has Not Improved Percentage of Non-Index Equity Funds Outperforming for Three-Year Rolling Period, 2004–2018 Lastly, in a world where index funds bias prices, we should expect to see evidence of such an impact across an index fund’s holdings. In other words, there should be more uniformity in the returns for securities within the same index as inflows drive prices up uniformly (and outflows drive prices down). Taking the S&P 500 Index as an example, however, we see that this has not been the case. The S&P 500 is a widely tracked index with over $9.9 trillion USD indexed or benchmarked to the index and with indexed assets comprising approximately $3.4 trillion USD of this total. Exhibit 4 shows that in 2008, a year of large net outflows and an index return of –37.0%, the constituent returns ranged from 39% to –97%. This exhibit also shows that in 2017, a year of large net inflows and a positive index return of 21.8%, the constituent returns ranged from 133.7% to –50.3%. We would also expect that constituents with similar weighting in traditional market cap-weighted indices would have similar returns. In 2017, Amazon and General Electric returned 56.0% and –42.9%, respectively, despite each accounting for approximately 1.5% of the S&P 500 Index. Exhibit 4. Range of S&P 500 Index Constituent Returns Conclusion Despite the increased popularity of index-based approaches, the data continue to support the idea that markets are working. Annual trading volume continues to be in line with prior years, indicating that market participant transactions are still driving price discovery. The majority of active mutual fund managers continue to underperform, suggesting that the rise of indexing has not made it easier to outguess market prices. Prices and returns of individual holdings within indices are not moving in lockstep with asset flows into index funds. Lastly, while naysayers will likely continue to point to indexing as a hidden danger in the market, it is important that investors keep in mind that index funds are still a small percentage of the diverse array of investor types. Investors can take comfort in knowing that markets are still functioning; willing buyers and sellers continue to meet and agree upon prices at which they desire to transact. It is also important to remember that while indexing has been a great financial innovation for many, it is only one solution in a large universe of different investment options. All data is from sources believed to be reliable but cannot be guaranteed or warranted. This information is intended for educational purposes, and it is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any particular security, products, or services. No one should assume that any discussion or information contained in this material serves as a receipt of, or as a substitute for, personalized investment, tax or legal advice. Diversification does not eliminate the risk of market loss. Investment risks include loss of principal and fluctuating value. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Indices are not available for direct investment; therefore, their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio.

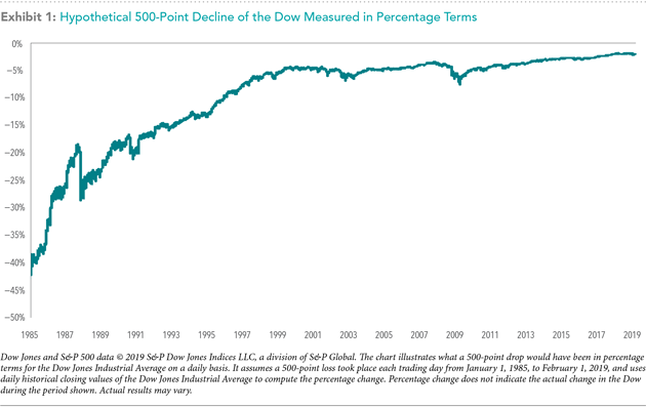

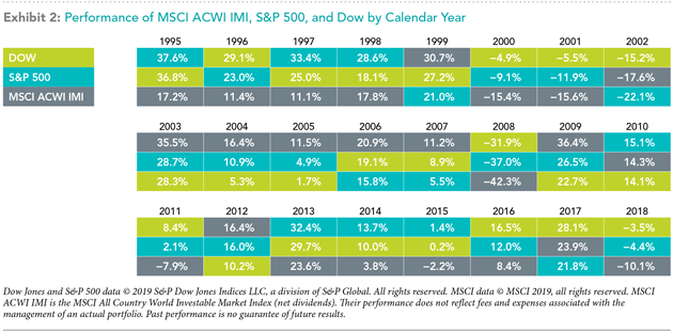

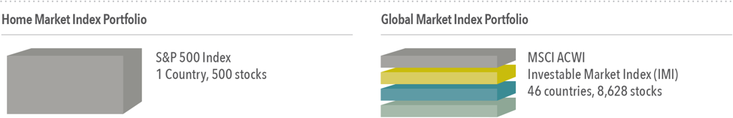

Appendix The Index Boogyman Derivative: A financial instrument whose value is based on an underlying asset or security. Options Contract: An options contract is an agreement between two parties to facilitate a potential transaction on an underlying security at a preset price. Futures: A financial contract obligating the buyer to purchase an asset or a seller to sell an asset at a predetermined future time and price. Active Manager Performance Has Not Improved: Options, futures, and corporate action data are from Bloomberg LP. Options contact volume is the sum of the 2018 daily average put and call volume of options on the S&P 500 Index, Russell 2000 Index, MSCI EAFE Index, and MSCI Emerging Markets Index. Equity futures volume is equal to total 2018 futures volume traded divided by 252, where annual volume traded is estimated as the sum of monthly volume times month-end contract value for S&P 500 Mini futures, Russell 2000 Mini futures, MSCI EAFE Mini futures, and MSCI Emerging Markets Mini futures. IPO, seasoned equity offering, and share repurchase data are based on Bloomberg corporate actions data and include countries that are eligible for Dimensional investment. Equity mutual fund outperformance percentages are shown for the three-year periods ending December 31 of each year, 2004–2018. Each sample includes equity funds available at the beginning of the three-year period. Outperformers are funds with return observations for every month of the three-year period whose cumulative net return over the period exceeded that of their respective Morningstar category index as of the start of the period. US-domiciled non-Dimensional mutual fund data is from Morningstar. Dimensional fund data provided by the fund accountant. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. For more methodology details, see the latest Mutual Fund Landscape brochure. Range of S&P 500 Index Constituent Returns: Upper chart includes 2008 total returns for constituent securities in the S&P 500 Index as of December 31, 2007. Lower chart includes 2017 total returns for constituent securities in the S&P 500 Index as of December 31, 2016. Excludes securities that delisted or were acquired during the year. Source: S&P data ©2019 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global. For illustrative purposes only. Indices are not available for direct investment; therefore, their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio. Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors LP. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. There is no guarantee an investing strategy will be successful. Investing involves risks including possible loss of principal. Diversification does not eliminate the risk of market loss. Indices are not available for direct investment. Their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio. All expressions of opinion are subject to change. This article is distributed for informational purposes, and it is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any particular security, products, or services. Investors should talk to their financial advisor prior to making any investment decision. Eugene Fama and Ken French are members of the Board of Directors of the general partner of, and provide consulting services to, Dimensional Fund Advisors LP. A quick online search for “Dow rallies 500 points” yields a cascade of news stories with similar titles, as does a similar search for “Dow drops 500 points.” These types of headlines may make little sense to some investors, given that a “point” for the Dow and what it means to an individual’s portfolio may be unclear. The potential for misunderstanding also exists among even experienced market participants, given that index levels have risen over time and potential emotional anchors such as a 500-point move do not have the same impact on performance as they used to. With this in mind, we examine what a point move in the Dow means and the impact it may have on an investment portfolio. IMPACT OF INDEX CONSTRUCTION The Dow Jones Industrial Average was first calculated in 1896 and currently consists of 30 large cap US stocks. The Dow is a price-weighted index, which is different than more common market capitalization-weighted indices.1 An example may help put this difference in weighting methodology in perspective. Consider two companies that have a total market capitalization of $1,000. Company A has 1,000 shares outstanding that trade at $1 each, and Company B has 100 shares outstanding that trade at $10 each. In a market capitalization-weighted index, both companies would have the same weight since their total market caps are the same. However, in a price-weighted index, Company B would have a larger weight due to its higher stock price. This means that changes in Company B’s stock would be more impactful to a price-weighted index than they would be to a market cap-weighted index. The relative advantages and disadvantages of these methodologies are interesting topics themselves, but the main purpose of discussing the differences in this context is to point out that design choices can have an impact on index performance. Investors should be aware of this impact when comparing their own portfolios’ performance to that of an index. HEADLINES VS. REALITY Movements in the Dow are often communicated in units known as points, which signify the change in the index level. Investors should be cautious when interpreting headlines that reference point movements, as a move of, say, 500 points in either direction is less meaningful now than in the past largely because the overall index level is higher today than it was many years ago. Exhibit 1 plots what a decline of this magnitude has meant in percentage terms over time. A 500-point drop in January 1985, when the Dow was near 1,300, equated to a nearly 39% loss. A 500-point drop in December 2003, when the Dow was near 10,000, meant a much smaller 5% decline in value. And a 500-point drop in early December 2018, when the Dow hovered near 25,000, resulted in a 2% loss. HOW DOES THE DOW RELATE TO YOUR PORTFOLIO? While the Dow and other indices are frequently interpreted as indicators of broader stock market performance, the stocks composing these indices may not be representative of an investor’s total portfolio. For context, the MSCI All Country World Investable Market Index (MSCI ACWI IMI) covers just over 8,700 large, mid, and small cap stocks in 23 developed and 24 emerging markets countries with a combined market cap of more than $50 trillion. The S&P 500 Index includes 505 large cap US stocks with approximately $23.8 trillion in combined market cap.2 The Dow is a collection of 30 large cap US stocks with a combined market cap of approximately $6.8 trillion.3 Even though the MSCI ACWI IMI, S&P 500, and Dow are all stock market indices, each one tracks different segments of the market, so their performance can differ significantly over time, as shown in Exhibit 2. Since 1995, the Dow has outperformed the S&P 500 and MSCI ACWI IMI by an average of 0.5% and 3.3%, respectively (based on calendar year returns). However, relative performance in individual years can be much different. For example, in 1997, the Dow underperformed the S&P 500 by 8.4% but outperformed the MSCI ACWI IMI by 13.9%. It is also important to note that some investors may be concerned about other asset classes besides stocks. Depending on investor needs, a diversified portfolio may include a mix of global stocks, bonds, commodities, and any number of other assets not represented in a stock index. A portfolio’s performance should always be evaluated within the context of an investor’s specific goals. Understanding how a personal portfolio compares to broadly published indices like the Dow can give investors context about how headlines apply to their own situation. CONCLUSION News headlines are often written to grab attention. A headline publicizing a 500-point move in the Dow may trigger an emotional response and, depending on the direction, sound either exciting or ominous enough to warrant reading the article. However, after digging further, we can see that the insights such headlines offer may be limited, especially if investors hold portfolios designed and managed daily to meet their individual goals, needs, and preferences in a broadly diversified and cost-effective manner. Appendix

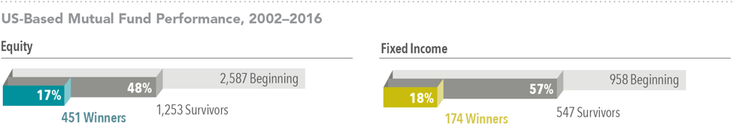

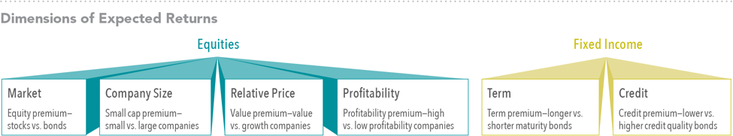

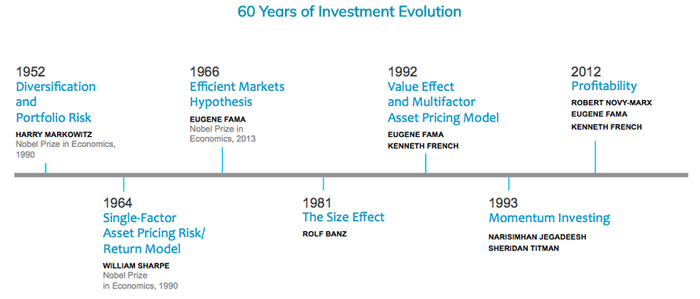

1. Market capitalization is the product of price and shares outstanding. 2. 500 companies are included in the S&P 500 Index. However, because some of these companies have multiple classes of stock that meet the requirements for inclusion, the total number of stocks tracked by the index is 505. 3. Market cap data as of January 31, 2019. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. This information is provided for educational purposes only and should not be considered. investment advice or a solicitation to buy or sell securities. There is no guarantee an investing strategy will be successful. Investing involves risks including possible loss of principal. Diversification does not eliminate the risk of market loss. Dimensional Fund Advisors LP is an investment advisor registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission. When selecting strategies for their portfolios, investors are often tempted to seek out the latest and greatest investment opportunities. Over the years, these approaches have sought to capitalize on developments such as the perceived relative strength of particular geographic regions, technological changes in the economy, or the popularity of different natural resources. But long-term investors should be aware that letting short-term trends influence their investment approach may be counterproductive. As Nobel laureate Eugene Fama said, “There’s one robust new idea in finance that has investment implications maybe every 10 or 15 years, but there’s a marketing idea every week.” WHAT’S HOT BECOMES WHAT’S NOT Looking back at some investment fads over recent decades can illustrate how often trendy investment themes come and go. In the early 1990s, attention turned to the rising “Asian Tigers” of Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan. A decade later, much was written about the emergence of the “BRIC” countries of Brazil, Russia, India, and China and their new place in global markets. Similarly, funds targeting hot industries or trends have come into and fallen out of vogue. In the 1950s, the “Nifty Fifty” were all the rage. In the 1960s, “go‑go” stocks and funds piqued investor interest. Later in the 20th century, growing belief in the emergence of a “new economy” led to the creation of funds poised to make the most of the rising importance of information technology and telecommunication services. During the 2000s, 130/30 funds, which used leverage to sell short certain stocks while going long others, became increasingly popular. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, “Black Swan” funds, “tail-risk-hedging” strategies, and “liquid alternatives” abounded. As investors reached for yield in a low interest rate environment in the following years, other funds sprang up that claimed to offer increased income generation, and new strategies like unconstrained bond funds proliferated. More recently, strategies focused on peer-to-peer lending, cryptocurrencies, and even cannabis cultivation and private space exploration have become more fashionable. In this environment, so-called “FAANG” stocks and concentrated exchange-traded funds with catchy ticker symbols have also garnered attention among investors. THE FUND GRAVEYARD Unsurprisingly, however, numerous funds across the investment landscape were launched over the years only to subsequently close and fade from investor memory. While economic, demographic, technological, and environmental trends shape the world we live in, public markets aggregate a vast amount of dispersed information and drive it into security prices. Any individual trying to outguess the market by constantly trading in and out of what’s hot is competing against the extraordinary collective wisdom of millions of buyers and sellers around the world. With the benefit of hindsight, it is easy to point out the fortune one could have amassed by making the right call on a specific industry, region, or individual security over a specific period. While these anecdotes can be entertaining, there is a wealth of compelling evidence that highlights the futility of attempting to identify mispricing in advance and profit from it. It is important to remember that many investing fads, and indeed, most mutual funds, do not stand the test of time. A large proportion of funds fail to survive over the longer term. Of the 1,622 fixed income mutual funds in existence at the beginning of 2004, only 55% still existed at the end of 2018. Similarly, among equity mutual funds, only 51% of the 2,786 funds available to US-based investors at the beginning of 2004 endured. WHAT AM I REALLY GETTING? When confronted with choices about whether to add additional types of assets or strategies to a portfolio, it may be helpful to ask the following questions: 1. What is this strategy claiming to provide that is not already in my portfolio? 2. If it is not in my portfolio, can I reasonably expect that including it or focusing on it will increase expected returns, reduce expected volatility, or help me achieve my investment goal? 3. Am I comfortable with the range of potential outcomes? If investors are left with doubts after asking any of these questions, it may be wise to use caution before proceeding. Within equities, for example, a market portfolio offers the benefit of exposure to thousands of companies doing business around the world and broad diversification across industries, sectors, and countries. While there can be good reasons to deviate from a market portfolio, investors should understand the potential benefits and risks of doing so. In addition, there is no shortage of things investors can do to help contribute to a better investment experience. Working closely with a financial advisor can help individual investors create a plan that fits their needs and risk tolerance. Pursuing a globally diversified approach; managing expenses, turnover, and taxes; and staying disciplined through market volatility can help improve investors’ chances of achieving their long-term financial goals. CONCLUSION Fashionable investment approaches will come and go, but investors should remember that a long-term, disciplined investment approach based on robust research and implementation may be the most reliable path to success in the global capital markets. Appendix

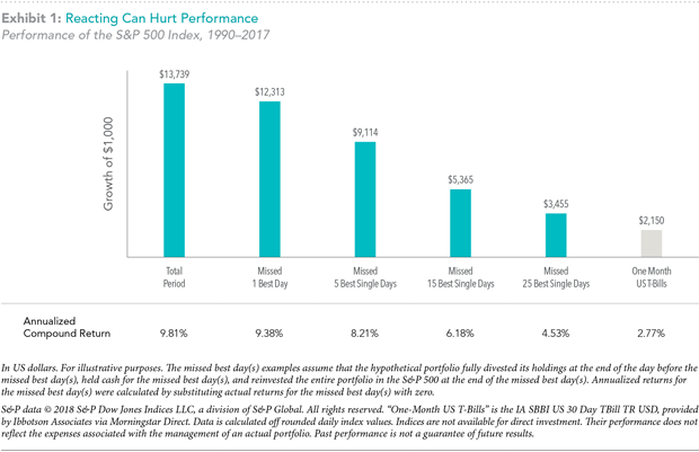

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. This information is provided for educational purposes only and should not be considered investment advice or a solicitation to buy or sell securities. There is no guarantee an investing strategy will be successful. Diversification does not eliminate the risk of market loss. Eugene Fama is a member of the Board of Directors of the general partner of, and provides consulting services to, Dimensional Fund Advisors LP. Dimensional Fund Advisors LP is an investment advisor registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission. As much as I value the unfettered access to information the internet provides, I recognize the potential harm that too much information can cause. Take, for example, a friend of mine, who was experiencing some troubling medical symptoms. Typing her symptoms into a search engine led to an evening of research and mounting consternation. By the end of the night, the vast quantity of unfiltered information led her to conclude that something was seriously wrong. One of the key characteristics that distinguishes an expert is their ability to filter information and make increasingly refined distinctions about the situation at hand. For example, you might describe your troubling symptoms to a doctor simply as a pain in the chest, but a trained physician will be able to ask questions and test several hypotheses before reaching the conclusion that rather than having the cardiac arrest you suspected, you have something completely different. While many of us may have the capacity to elevate our understanding to a high level within a chosen field, reaching this point takes time, dedication, and experience. My friend, having convinced herself that something was seriously wrong, booked an appointment with a physician. The doctor asked several pertinent questions, performed some straightforward tests, and recommended the following treatment plan: reassurance and education. Not surgery. Not drugs. But an understanding of why and how she had experienced her condition. The consultative nature of a relationship with a trusted professional—both when a situation arises and as we progress through life—is one of the key benefits that an expert can provide. There are striking parallels with the work of a professional financial advisor. The first responsibility of the doctor or advisor is to understand the person they’re serving so that they can fully assess their situation. Once the plan is underway, the role of the professional is to monitor the person’s situation, evaluate if the course of action remains appropriate, and help to maintain the discipline required for the plan to work as intended. Like my friend’s doctor, advisors may have experienced conversations with clients that are triggered by news reports or informed by unqualified sources. In some cases, all that is required to help put the client’s mind at ease is a reminder to focus on what is in their control as well as providing reassurance and (re)education that they have a financial plan in place that is helping them move toward their objectives. The benefits of working with the right advisor are demonstrated through the ability to both help clients pursue their financial goals and to help them have a positive experience along the way. Trouble might arise when we confuse simple and complex conditions. Probably no harm is done when a person, recognizing the onset of a common cold, takes cold medicine, drinks plenty of fluids, and rests. But had my self-diagnosing friend not made an appointment with a specialist, and instead moved from self-diagnosis to self-medication, she may have caused herself real harm. Similarly, thinking that all aspects of your own financial situation can be handled through a basic internet search or casual conversation with a friend might result in a less than optimal financial outcome. Without the guidance of an advisor, the self-medicating investor might overreact to short-term market volatility by selling some of their investments. In doing so, they risk missing out on some of the best days since there is no reliable way to predict when positive returns in equity markets will occur.1 One might think that missing a few days of strong returns would not make much difference over the long term. But, as illustrated in Exhibit 1, had an investor missed the 25 single best days in the world’s biggest equity market, the US, between 1990 and the end of 2017, their annualized return would have dropped from 9.81% to 4.53%. Such an outcome can have a major impact on an investor’s financial “treatment” plan. Improving someone’s financial health is a lot like improving their physical health. The challenges associated with pursuing a better financial outcome include diagnosis of the current situation, development of the appropriate course of action, and sticking with the treatment plan. Many advisors are trained on the intricacies of complex financial situations and work to understand how their clients feel about money and how their clients might react to future events. By providing the prescription of reassurance and education over time, we believe the right advisor can play a vital and irreplaceable role in investors’ lives. Article by David R. Jones EMEA and Vice President, Dimensional Fund Advisors

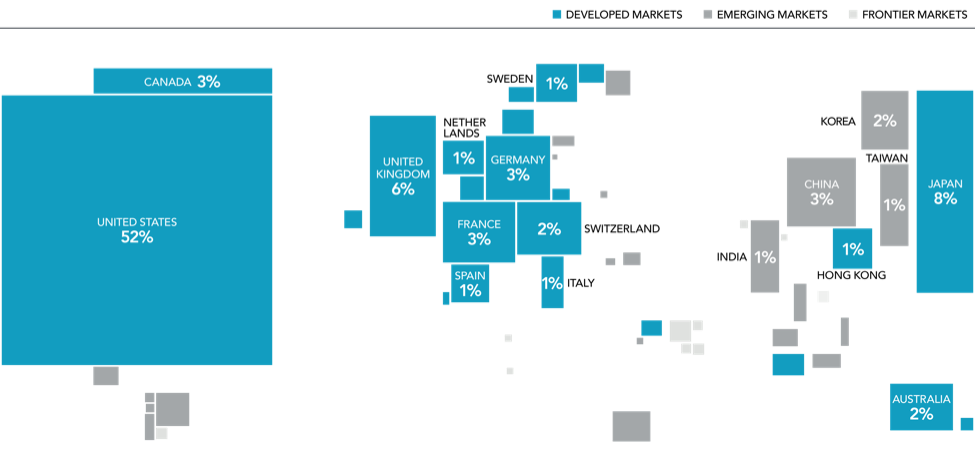

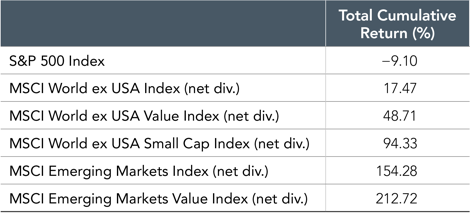

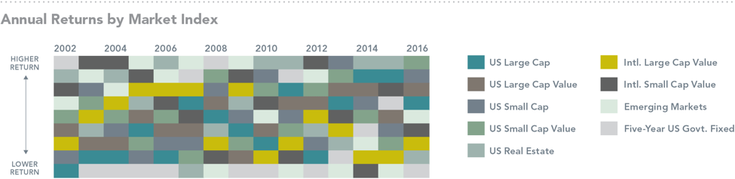

1. The 2018 Mutual Fund Landscape report compiled by Dimensional showed that for the 15-year period through 2017, only 14% of US equity mutual funds and 13% of US fixed income mutual funds survived and outperformed their benchmark after costs. Refer to us.dimensional.com/perspectives/mutual-fund-landscape-2018 for more information. Dimensional makes no representation as to the suitability of any advisor, and we do not endorse, recommend, or guarantee the services of any advisor, including those in the Find an Advisor portion of our website. Investors should carefully and thoroughly evaluate any advisor whom they consider hiring or working with. There is no guarantee investment strategies will be successful. Investing involves risks, including possible loss of principal. There is always the risk that an investor may lose money. A long-term investment approach cannot guarantee a profit. Results for other time periods, including shorter time periods, may include losses. As 2019 approaches, and with US stocks outperforming non-US stocks in recent years, some investors have again turned their attention towards the role that global diversification plays in their portfolios. For the five-year period ending October 31, 2018, the S&P 500 Index had an annualized return of 11.34% while the MSCI World ex USA Index returned 1.86%, and the MSCI Emerging Markets Index returned 0.78%. As US stocks have outperformed international and emerging markets stocks over the last several years, some investors might be reconsidering the benefits of investing outside the US. While there are many reasons why a US-based investor may prefer a degree of home bias in their equity allocation, using return differences over a relatively short period as the sole input into this decision may result in missing opportunities that the global markets offer. While international and emerging markets stocks have delivered disappointing returns relative to the US over the last few years, it is important to remember that: 1. Non-US stocks help provide valuable diversification benefits. 2. Recent performance is not a reliable indicator of future returns. 2. Recent performance is not a reliable indicator of future returns. There’s a World of Opportunity in Equities The global equity market is large and represents a world of investment opportunities. As shown in Exhibit 1, nearly half of the investment opportunities in global equity markets lie outside the US. Non-US stocks, including developed and emerging markets, account for 48% of world market capitalization and represent thousands of companies in countries all over the world. A portfolio investing solely within the US would not be exposed to the performance of those markets. Exhibit 1. World Equity Market Capitalization The Lost Decade We can examine the potential opportunity cost associated with failing to diversify globally by reflecting on the period in global markets from 2000–2009. During this period, often called the “lost decade” by US investors, the S&P 500 Index recorded its worst ever 10year performance with a total cumulative return of –9.1%. However, looking beyond US large cap equities, conditions were more favorable for global equity investors as most equity asset classes outside the US generated positive returns over the course of the decade. (See Exhibit 2.) Expanding beyond this period and looking at performance for each of the 11 decades starting in 1900 and ending in 2010, the US market outperformed the world market in five decades and underperformed in the other six. This further reinforces why an investor pursuing the equity premium should consider a global allocation. By holding a globally diversified portfolio, investors are positioned to capture returns wherever they occur. Exhibit 2. Global Index Returns, January 2000–December 2009 Pick a Country? Are there systematic ways to identify which countries will outperform others in advance? Exhibit 3 illustrates the randomness in country equity market rankings (from highest to lowest) for 22 different developed market countries over the past 20 years. This graphic conveys how difficult it would be to execute a strategy that relies on picking the best country and the resulting importance of diversification. Exhibit 3. Equity Returns of Developed Markets In addition, concentrating a portfolio in any one country can expose investors to large variations in returns. The difference between the best and worst‐performing countries can be significant. For example, since 1998, the average return of the best‐performing developed market country was approximately 44%, while the average return of the worst performing country was approximately –16%. Diversification means an investor’s portfolio is unlikely to be the best or worst performing relative to any individual country, but diversification also provides a means to achieve a more consistent outcome and more importantly helps reduce and manage catastrophic losses that can be associated with investing in just a small number of stocks or a single country. A Diversified Approach Over long periods of time, investors may benefit from consistent exposure in their portfolios to both US and non‐US equities. While both asset classes offer the potential to earn positive expected returns in the long run, they may perform quite differently over short periods. While the performance of different countries and asset classes will vary over time, there is no reliable evidence that this performance can be predicted in advance. An approach to equity investing that uses the global opportunity set available to investors can provide diversification benefits as well as potentially higher expected returns. Appendix

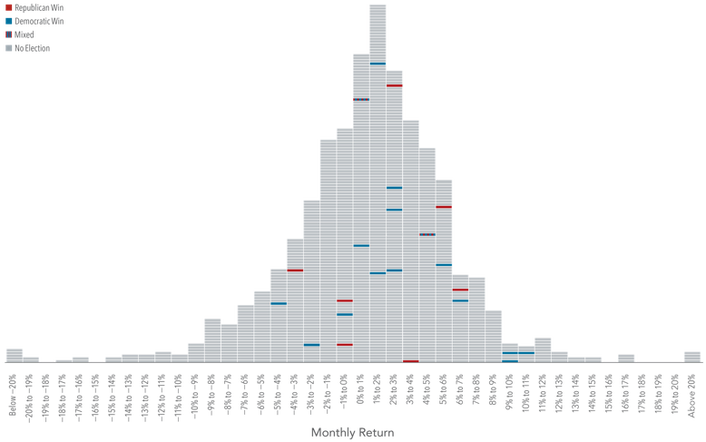

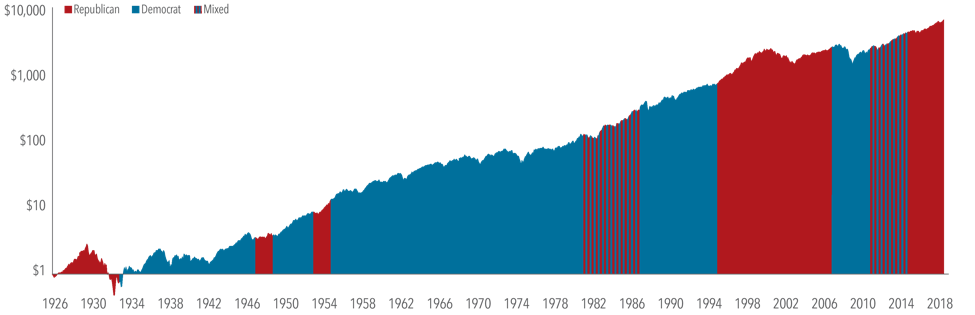

[1]. The total market value of a company’s outstanding shares computed as price times shares outstanding. [2]. Source: Annual country index return data from the Dimson-Marsh-Staunton (DMS) Global Returns Data, provided by Morningstar, Inc. World Equity Market Capitalization: As of December 31, 2017. Data provided by Bloomberg. Market cap data is free-float adjusted and meets minimum liquidity and listing requirements. China market capitalization excludes A-shares, which are generally only available to mainland China investors. For educational purposes; should not be used as investment advice. Global Index Returns: S&P data © 2018 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global. All rights reserved. MSCI data © MSCI 2018, all rights reserved. Indices are not available for direct investment. Index performance does not reflect expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Equity Returns of Global Markets: Source: MSCI country indices (net dividends) for each country listed. Does not include Israel, which MSCI classified as an emerging market prior to May 2010. MSCI data © MSCI 2018, all rights reserved. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Indices are not available for direct investment; therefore, their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio. Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors LP. Indices are not available for direct investment. Their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Diversification does not eliminate the risk of market loss.There is no guarantee investment strategies will be successful. Investing involves risks, including possible loss of principal. Investors should talk to their financial advisor prior to making any investment decision. All expressions of opinion are subject to change. This article is distributed for informational purposes, and it is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any particular security, products, or services. Investors should talk to their financial advisor prior to making any investment decision It’s almost Election Day in the US once again. For those who need a brief civics refresher, every two years the full US House of Representatives and one-third of the Senate are up for reelection. While the outcomes of the elections are uncertain, one thing we can count on is that plenty of opinions and prognostications will be floated in the days to come. In financial circles, this will almost assuredly include any potential for perceived impact on markets. But should long-term investors focus on midterm elections? MARKETS WORK We would caution investors against making short-term changes to a long-term plan to try to profit or avoid losses from changes in the political winds. For context, it is helpful to think of markets as a powerful information-processing machine. The combined impact of millions of investors placing billions of dollars’ worth of trades each day results in market prices that incorporate the aggregate expectations of those investors. This makes outguessing market prices consistently very difficult.[1] While surprises can and do happen in elections, the surprises don’t always lead to clear-cut outcomes for investors. The 2016 presidential election serves as a recent example of this. There were a variety of opinions about how the election would impact markets, but many articles at the time posited that stocks would fall if Trump were elected.[1] The day following President Trump’s win, however, the S&P 500 Index closed 1.1% higher. So even if an investor would have correctly predicted the election outcome (which was not apparent in pre-election polling), there is no guarantee that they would have predicted the correct directional move, especially given the narrative at the time. But what about congressional elections? For the upcoming midterms, market strategists and news outlets are still likely to offer opinions on who will win and what impact it will have on markets. However, data for the stock market going back to 1926 shows that returns in months when midterm elections took place did not tend to be that different from returns in any other month. Exhibit 1 shows the frequency of monthly returns (expressed in 1% increments) for the S&P 500 Index from January 1926–August 2018. Each horizontal dash represents one month, and each vertical bar shows the cumulative number of months for which returns were within a given 1% range (e.g., the tallest bar shows all months where returns were between 1% and 2%). The blue and red horizontal lines represent months during which a midterm election was held, with red meaning Republicans won or maintained majorities in both chambers of Congress, and blue representing the same for Democrats. Striped boxes indicate mixed control, where one party controls the House of Representatives, and the other controls the Senate, while gray boxes represent non-election months. This graphic illustrates that election month returns were well within the typical range of returns, regardless of which party won the election. Results similarly appeared random when looking at all Congressional elections (midterm and presidential) and for annual returns (both the year of the election and the year after). Exhibit 1. Midterm Elections and S&P 500 Index Returns, Histogram of Monthly Returns January 1926–August 2018 Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Indices are not available for direct investment; therefore, their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio. S&P data © 2018 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global. All rights reserved. IN IT FOR THE LONG HAUL While it can be easy to get distracted by month-to-month or even one-year returns, what really matters for long-term investors is how their wealth grows over longer periods of time. Exhibit 2 shows the hypothetical growth of wealth for an investor who put $1 in the S&P 500 Index in January 1926. Again, the chart lays out party control of Congress over time. And again, both parties have periods of significant growth and significant declines during their time of majority rule. However, there does not appear to be a pattern of stronger returns when any specific party is in control of Congress, or when there is mixed control for that matter. Markets have historically continued to provide returns over the long run irrespective of (and perhaps for those who are tired of hearing political ads, even in spite of) which party is in power at any given time. Exhibit 2. Hypothetical Growth of $1 Invested in the S&P 500 Index and Party Control of Congress January 1926–August 2018 Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Indices are not available for direct investment; therefore, their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio. S&P data © 2018 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global. All rights reserved. Equity markets can help investors grow their assets, and we believe investing is a long-term endeavor. Trying to make investment decisions based on the outcome of elections is unlikely to result in reliable excess returns for investors. At best, any positive outcome based on such a strategy will likely be the result of random luck. At worst, it can lead to costly mistakes. Accordingly, there is a strong case for investors to rely on patience and portfolio structure, rather than trying to outguess the market, to pursue investment returns. Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors LP.

Indices are not available for direct investment. Their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Diversification does not eliminate the risk of market loss. There is no guarantee investment strategies will be successful. Investing involves risks, including possible loss of principal. Investors should talk to their financial advisor prior to making any investment decision. There is always the risk that an investor may lose money. A long-term investment approach cannot guarantee a profit. All expressions of opinion are subject to change. This article is distributed for informational purposes, and it is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any particular security, products, or services. Investors should talk to their financial advisor prior to making any investment decision. [1]. This is known as the efficient market theory, which postulates that market prices reflect the knowledge and expectations of all investors and that any new development is instantaneously priced into a security. [2]. Examples include: “A Trump win would sink stocks. What about Clinton?” CNN Money, 10/4/16, “What do financial markets think of the 2016 election?” Brookings Institution, 10/21/16, “What Happens to the Markets if Donald Trump Wins?” New York Times, 10/31/16. What do attorneys, psychiatrists, tax & financial professionals all have in common? While it may feel like a punchline is coming, what I’m referring to is what they offer. Their primary product is intellectual capital, something intangible that we can’t necessarily feel or touch. Patients/clients are tasked with quantifying the value of it. The question is: How? I could argue the following insight is applicable to lots of professions, but coming from a guy who runs a wealth management firm, I’ll keep this commentary on the financial side of the spectrum. Numerous studies have been conducted in an attempt to broadly measure the monetary benefits of working with an advisor. Here, I’ll walk through a simple critical thinking exercise, purely designed to help investors make informed decisions. First, it’s important to point out the human element. Based on our experiences, we all have biases when it comes to interpreting value. Most of us possess situational skepticism’s thanks in part to a daily dosage of fly-by-night quick fixes, aimed at lightening our pockets. If you believe that all physiatrists are quacks, all lawyers are ambulance chasers, or all financial services professionals are salespeople, you probably have a preconception which will inevitably factor into how you value their advice. Personal Due Diligence: A Litmus Test for Seeking Financial Advice

Let’s break those down a bit further. Experience: The question really isn’t whether or not you can do it yourself. The question that’s more applicable is can you do it “well”? The biggest challenge I commonly see with do-it-yourself investors stems from understanding how and why financial planning and investment management are related. After analyzing thousands of portfolios through the years, here are some of the most common deficiencies in no particular order.

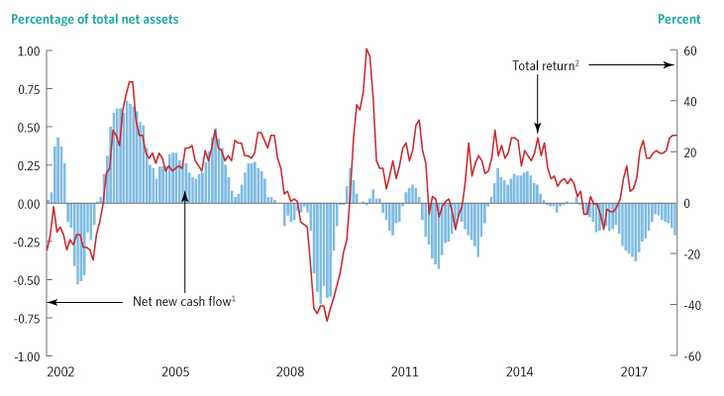

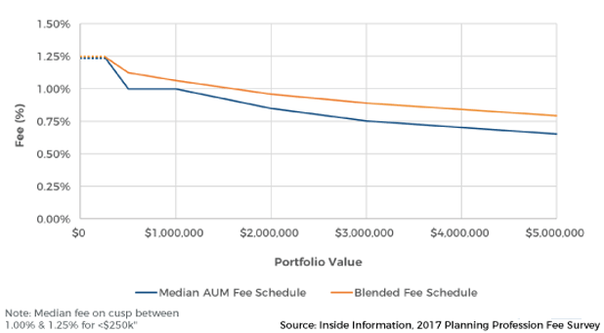

Time: Markets and investment vehicles are constantly evolving. Therefore, investment portfolios should evolve as well. We’re always learning more about expected return and where it comes from. As we do, investment providers are quick to adapt, offering solutions with incremental improvements. The problem is, there’s lots of them. At last check, there were around 7,000 mutual funds and over 2,000 ETF’s (Exchange Traded Funds) in existence. This underscores the importance of recognizing that financial planning isn’t a one-time thing but an ongoing event that requires adjustment with life events. Investments, taxation, insurance and estate planning all need to be working in concert. Collectively, this amounts to a lot more time than many realize, which often leads to a lack of attention. Desire: Does the on-going, in-depth examination of your financial situation interest you or not? If you don’t enjoy working on cars, you’re probably not keen on repairing your own transmission. The concept of hiring professionals in different capacities effectively allows us to spend time doing what we enjoy, or what we do best. Discipline: This goes way beyond the idea of having someone there to hold your hand. Yes, psychology plays a role. However, discipline runs deeper than simply resisting reactions to every market movement. We know it applies to investing, but it must also apply to financial planning. Purchasing a home, having a child, changing jobs, marriage, college, retirement etc. are life events that require sound financial adjustments. When it comes to managing your portfolio, the behavioral impact on investing is well documented. It’s easy enough to say, “disciplined investors have historically been rewarded for maintaining that discipline.” However, doing so requires not only a steady hand but also a dedicated understanding of capital markets and how a host of different scenarios affect your unique situation. We've been through around half a dozen bull and bear markets over the last 30 years. Needless to say, long-term investors are likely to experience a bunch of them over a lifetime. Net New Cash Flow to Equity Mutual Funds Typically Is Related to World Equity Returns Monthly, 2002-2017 Net new cash flow is the percentage of previous month-end equity mutual fund total net assets, plotted as a six-month moving average. The total return on equities is measured as the year-over-year percent change in the MSCI All Country World Daily Gross Total Return Index. Sources: Investment Company Institute, MSCl, and Bloomberg The history of mutual fund cash flows through the years paints a difficult picture for investor behavior. In 2008, we saw large outflows in equity mutual funds right around the bottom of the market. Subsequently, we saw positive cash flows in the ladder part of 2009 and into 2010 long after markets went into recovery mode. Remember the age old adage about being a successful investor “Buy Low, Sell High”? Well, the opposite often happens and emotional discipline is frequently the culprit. Contingency: Confidence in all of the above isn’t enough to ensure a favorable outcome. Many overlook the capacity of their heirs to make sound decisions in the event that they no longer can. Death, disability or incapacity impacts everyone. Prudence dictates an analysis of capable contingencies. Professional Due Diligence: Aptitude, Delivery, Services, Comparatives When weighing the value of financial advice, it’s critical to understand the substantial differences between types of financial advisors. Many lack the credentials or even legal authority qualify what they offer as advice in the first place. Brokers are not advisors and Fee-Based is not the same as Fee-Only. Here, I’ll focus on Fee-Only fiduciary advice, the industry standard for placing the clients’ interests first 100% of the time. Aptitude: This encompasses the combination of experience, education, and reputation. Experience: In finance, there’s little substitute for the seasoned experience an advisor receives through a variety of different market cycles and with a variety of different types of clients. Education: Undergraduate business degree’s and MBA’s demonstrate a commitment to education. Industry designations such as CFP® (Certified Financial Planner) or CFA (Chartered Financial Analyst) further indicate levels of expertise. Reputation: Any due diligence should begin with a baseline evaluation of regulatory history (run a background check). Also, look for specific examples of expertise. Many advisors are active contributors to media outlets. Read columns or interviews to get insight into their investment philosophy or planning approach. Tip: Start with the firm’s website. Services: Carefully understanding what’s included and what isn’t is essential because service offerings are all over the map. Does the advisor provide one-time financial planning services, ongoing investment management services, the combination of both? How much access do you have to professionals? What types of reports and online access do you receive? Delivery: How do you want to interact with an advisor? There’s a cost to doing business. Face to face interaction is costlier than email, phone or video. Therefore, it’s reasonable to expect a premium on face to face interaction. Comparatives: After determining what’s included and what isn’t you can then analyze the market rate for these services. Recent study Conclusion A comprehensive approach to quantifying value helps to diligently explore elements that often get overlooked. Investors should strive to understand themselves, their strengths and limitations before jumping straight into the evaluation of an advisory firm. Starting off with a basic Litmus test helps to solidify the rationale for seeking or not seeking advice. It’s about placing a timeline of personal due diligence in front of professional due diligence with the goal of making informed decisions. Our daily lives are crammed with punchlines and parables. Investing has a language of sayings and catchphrases of its own. Some encourage action, others espouse knowledge. This column highlights some of the more well known. Good, bad or indifferent.

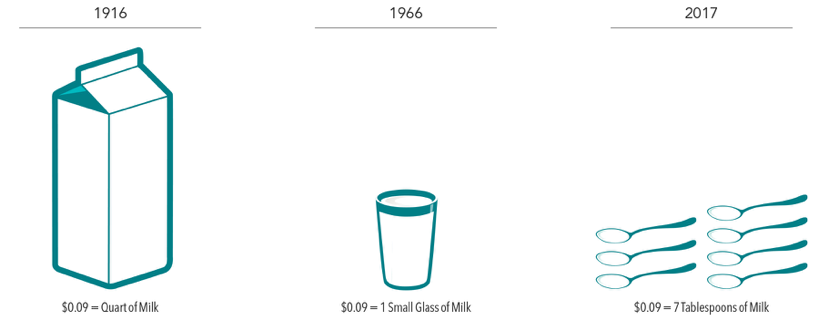

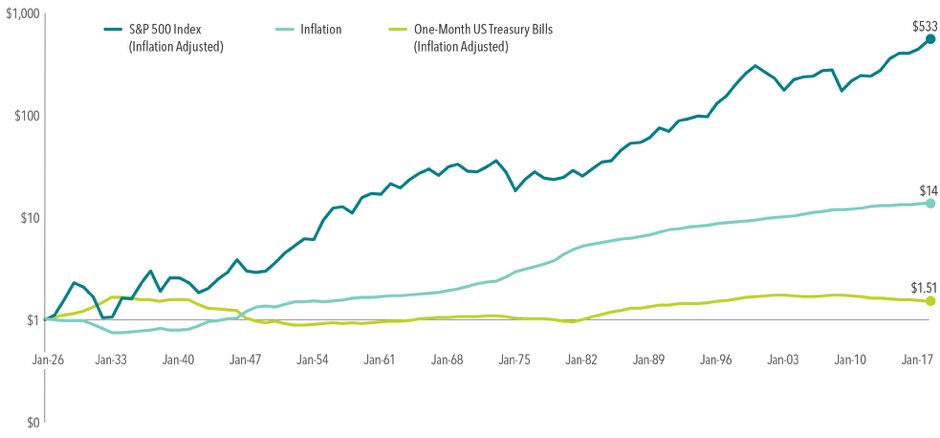

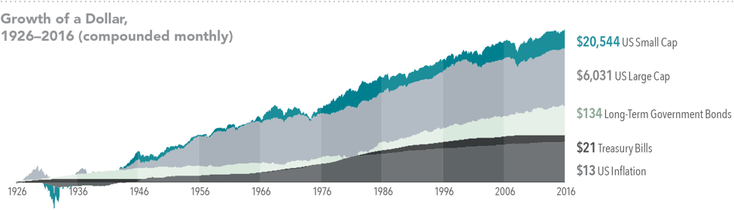

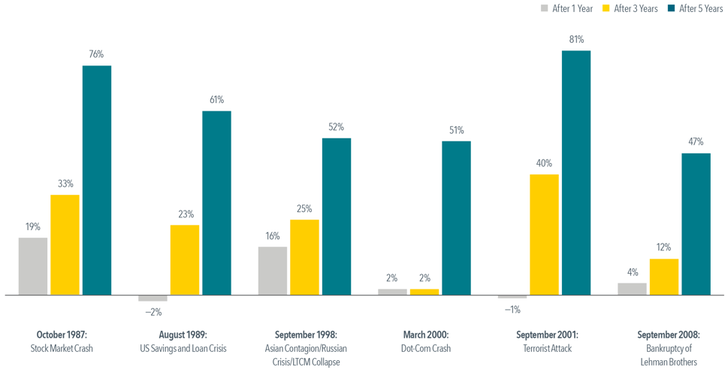

The Hazardous We begin with what Sir John Templeton called “The four most dangerous words in investing: 'this time it's different.’” There are different interpretations of the quote but most regularly it applies to ignoring history at your own peril. When in reference to the stock market, there’s always going to be unforeseen ups and downs but overtime more ups than downs. Long term disciplined investors have historically been rewarded for maintaining that discipline despite the opinions of pundits and prognosticators. Buy low, sell high. It’s probably the most simplistic expression, yet the most difficult in practical application. Namely, buying when things appear bleakest and selling when things look great isn’t exactly a natural human inclination. In fact, looking at equity mutual fund cash flows through the years, exactly the opposite is the tendency. The last market downturn saw massive outflows in 2008, reversing course in the ladder part of 2009 well after markets went into recovery mode. I got in early. Usually, you see this in reference to a perceived new investment idea. The issue is, it’s almost impossible to quantify the statement thanks to the speed at which information travels and is incorporated into prices. Simply put, an investor really has no way of knowing if they got in early and should most often work under the assumption that prices reflect all available information. Similarly, “Buy the rumor, sell the news” speaks to speculation on what could happen, while failing to comprehend how much of the “rumor” has already been factored into current prices. “I’m waiting for the pullback” suggests that prices in some way are inaccurate and an investor has the foresight to time the market perfectly in order to take advantage of a subsequent uptick. The perils of attempting to time the market are well documented. The problem is making a single accurate decision isn’t nearly good enough. To be a successful an investor would have to decide when to get in and when to get out multiple times over an investment lifetime. The trend is your friend. That is of course until it’s not, meaning- keep buying when it appears to be going up and start selling when it goes down. One of the biggest mistakes investors make is failing to recognize that markets operate on “news” which by definition is unpredictable or else it wouldn’t be news. Essentially, there’s no way of knowing what is a trend and what isn’t. It’s a market of stocks, not a stock market. This classic day trader proverb implies that you can always make money providing you pick the right stocks. The issue with stock speculation is the evidence of long term success isn’t remotely on the side of active traders. Bulls make money, bears make money, pigs get slaughtered. This demonstrates an active trader’s mentality that superior skill can make money in any market, but only within the confines of their own greed. Again, we see speculation on when to get in and when to get out, a short term mentality that requires the daunting task of accurately identifying when a stock is over or underpriced. On the flip side: Here’s some of the wisest I’d compare stock pickers to astrologers but I don’t want to bad mouth astrologers. Rarely at a loss for words, the father of modern finance and Nobel Prize winner Eugene Fama speaks to the difficulties in identifying stock miss pricings. Based on decades of data, studies have shown that the average actively managed dollar is far more likely to underperform the average passively managed dollar. Warren Buffet is probably the most quoted investor of our time with gems like “When the tide goes out, you see who’s swimming naked” in reference to having a lack of diversification in your portfolio when markets pull back. In these instances, concentrated exposures in any one specific investment can spell disaster for a portfolio. Other Buffet favorites include: “The most important quality for an investor is temperament, not intellect” and “Be fearful when others are greedy. Be greedy when others are fearful" both speaking to the well-known emotional tendencies of investors. Above all, patience and levelheadedness are two attributes that investors should hold in the highest regard. John Maynard Keynes’s famous line “Markets can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent” has been used to describe a variety of scenarios not limited to the disposition of investors and the unpredictable nature of markets. We’ve been through five different bull and bear markets over the last 27 years, each with significant variations in how long they lasted. Author of “The Intelligent Investor,” value investing pioneer Benjamin Graham spoke to "The investor's chief problem, even his worst enemy, is likely to be himself." Most investors have emotional attachments to hard earned money, which can lead to decisions that are detrimental to long term success. He also thought that “To be an investor you must be a believer in a better tomorrow.” It’s a basic prerequisite to believe that advancements in technology, standards of living, and ultimately profits will rise over time. Without this ideology, there would simply be no reason to invest. Index Investing pioneer and Vanguard founder John Bogle provided some simplistic advice in reference to having all your exposure to stocks "If you have trouble imagining a 20% loss in the stock market, you shouldn't be in stocks". It’s critical to thoroughly understand your risk tolerance for market fluctuation. As your exposure to stocks increases, generally speaking, so does the level of risk in your portfolio. An investor should never take more risk than they can sleep with at night. Nobel laureate Paul Samuelson felt "Investing should be more like watching paint dry or watching grass grow. If you want excitement, take $800 and go to Las Vegas." There’s a difference between investing and speculating. The whole idea of being an investor is to grow assets over the long term. Aligning long term investment growth with short term entertainment isn’t a heck of a lot different than gambling. Finally, a few warnings about the wisdom of Wall Street and giving too much credence to media pundits. “There seems to be an unwritten rule on Wall Street: If you don’t understand it, then put your life savings into it.” - Peter Lynch Many of the financial products coming out of Wall Street over the years are bought and sold on the premise of being the next hot thing. As rule of thumb, you should always know how your money is invested, complete with a thorough understanding of the potential risk, fee’s and liquidity associated with any investment vehicle. And Ex-Daily show host John Stewart on the 2008 market downturn: “If I’d only followed CNBC’s advice, I’d have a million dollars today. Provided I’d started with a hundred million dollars.” Don’t’ put too much stock in the daily commentary from talking heads whose job is to keep you reading, listening or watching. Instead, focus on your unique situation and look for help from qualified professionals who have your best interest in mind. It’s certainly not a comprehensive list but I hope you enjoyed it. The next time you hear one of these phrases remember to keep it in the proper context. When the prices of goods and services increase over time, consumers can buy fewer of them with every dollar they have saved. This erosion of the real purchasing power of wealth is called inflation. Inflation is an important element of investing. In many cases, the reason for saving today is to support future spending. Therefore, keeping pace with inflation is a crucial goal for many investors. To help understand inflation’s impact on purchasing power, consider the following illustration of the effects of inflation over time. In 1916, nine cents would buy a quart of milk. Fifty years later, nine cents would only buy a small glass of milk. And more than 100 years later, nine cents would only buy about seven tablespoons of milk. How can investors potentially prevent this loss of purchasing power from inflation over time? Exhibit 1. Your Money Today Will Likely Buy Less Tomorrow In US dollars. Source for 1916 and 1966: Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970/US Department of Commerce. Source for 2017: US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Economic Statistics, Consumer Price Index—US City Average Price Data. Investing for the long term and other “tips” As the value of a dollar declines over time, investing can help grow wealth and preserve purchasing power. Investors should know that over the long haul stocks have historically outpaced inflation, but there have also been short-term stretches where this has not been the case. For example, during the 17-year period from 1966–1982, the return of the S&P 500 Index was 6.8% before inflation, but after adjusting for inflation it was 0%. Additionally, if we look at the period from 2000–2009, the so-called “lost decade,” the return of the S&P 500 Index dropped from –0.9% before inflation to –3.4% after inflation. Despite some periods where stocks have failed to outpace inflation, one dollar invested in the S&P 500 Index in 1926, after accounting for inflation, would have grown to more than $500 of purchasing power at the end of 2017 and would have significantly outpaced inflation over the long run. The story for US Treasury bills (T-bills), however, is quite different. In many periods, T-bills were unable to keep pace with inflation, and an investor would have experienced an erosion of purchasing power. After adjusting for inflation, one dollar invested in T-bills in 1926 would have grown to only $1.51 at the end of 2017. Exhibit 2. Growth of $1, 1926–2017 S&P and Dow Jones data © 2018 Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global. All rights reserved. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Actual returns may be lower. Inflation is measured as changes in the US Consumer Price Index. While stocks are more volatile than T-bills, they have also been more likely to outpace inflation over long periods. The lesson here is that volatility is not the only type of risk that should concern investors. Ultimately, many investors may need to have some of their allocation in growth investments that outpace inflation to maintain their standard of living and grow their wealth. One additional tool available to investors who are concerned about both stock market volatility and inflation are Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS). TIPS are guaranteed by the US Treasury and as such are considered by the marketplace to have low risk of default. The Treasury issues TIPS with a variety of maturities, and these securities are easily bought and sold. Unlike traditional Treasury securities such as T-bills, TIPS are indexed to inflation to protect investors from an erosion in purchasing power. As inflation (measured by the consumer price index) rises, so does the par value of TIPS, while the interest rate remains fixed. This means that if inflation unexpectedly rises, the purchasing power of any principal invested in TIPS should also increase.[1] Although they may not offer the long-term growth opportunities that stocks do, their structure makes TIPS an effective risk management tool for investors who are concerned with managing uncertainty around future purchasing power. Conclusion Inflation is an important consideration for many long-term investors. By combining the right mix of growth and risk management assets, investors may be able to blunt the effects of inflation and grow their wealth over time. Remember, however, that inflation is only one consideration among many that investors must contend with when building a portfolio for the future. The right mix of assets for any investor will depend upon that investor’s unique goals and needs. A financial advisor can help investors weigh the impact of inflation and other important considerations when preparing and investing for the future. [1]. Market prices incorporate market participants’ expectations about the future. Therefore, market participants’ expectations about future inflation should be incorporated into current prices. These expectations are referred to as expected inflation. Unexpected inflation refers to unexpected changes in inflation that deviate from prior market expectations. Unexpected inflation should be considered a primary driver of inflation risk.

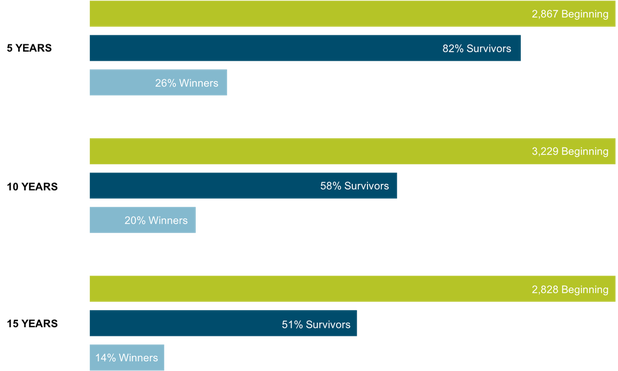

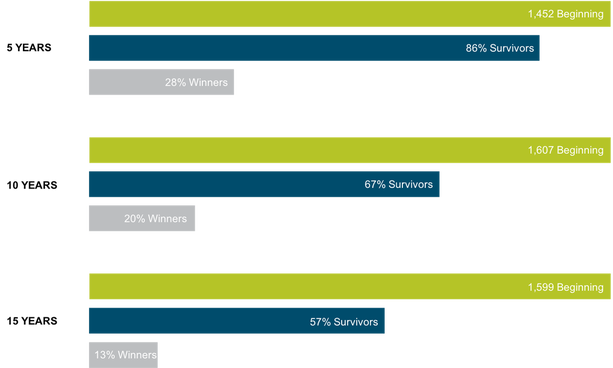

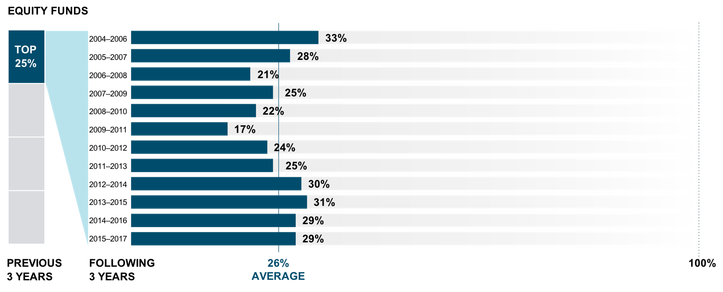

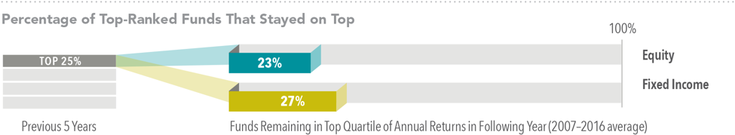

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors LP. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Indices are not available for direct investment. Their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio. There is no guarantee investment strategies will be successful. Investing involves risks including possible loss of principal. Investors should talk to their financial advisor prior to making any investment decision. There is always the risk that an investor may lose money. A long-term investment approach cannot guarantee a profit. All expressions of opinion are subject to change. This article is distributed for informational purposes, and it is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any particular security, products, or services. Investors should talk to their financial advisor prior to making any investment decision. Few Equity Funds Have Survived and Outperformed Performance periods ending December 31, 2017 Disappearing Funds The size of the mutual fund landscape masks the fact that many funds disappear each year, often due to poor investment performance. Investors may be surprised by how many mutual funds become obsolete over time. About half of the equity and fixed income funds were no longer available after 15 years. Including these non-surviving funds in the sample is an important part of assessing mutual fund manager performance. The evidence suggests that only a low percentage of funds in the original sample were “winners”—defined as those that both survived and outperformed benchmarks. Both survival and outperformance rates tended to fall as the time horizon expands. For the 15‑year period through 2017, only 14% of equity funds survived and outperformed their benchmarks. Few Fixed Income Funds Have Survived and Outperformed Fixed income fund performance periods ending December 31, 2017 This chart shows survivorship and outperformance for fixed income funds. Their survival rates were similar to those of equities for the same 5-, 10-, and 15-year periods. Over time, a declining percentage of fixed income funds from the beginning sample survived, and only a fraction of those surviving funds delivered winning performance. For the 15-year period through 2017, only 13% of fixed income funds survived and outperformed their benchmarks. Past Performance Is Not Enough to Predict Future Results Percentage of funds that were top-quartile performers in consecutive three-year period The Search for Persistence Some investors may resort to using track records as a guide to selecting funds, reasoning that a manager’s past success is likely to continue in the future. Does this assumption pay off? The research offers evidence to the contrary. The exhibit shows that among funds ranked in the top quartile (25%) based on previous three-year returns, a minority also ranked in the top quartile of returns over the following three-year period. This lack of persistence casts further doubt on the ability of managers to consistently gain an informational advantage on the market. For example, in 2017, only 29% of equity funds were ranked in the top quartile of performance in their category in both the previous period (2012–2014) and subsequent period (2015–2017). Over the 12 years through 2017, top-quartile persistence of three-year performers averaged 26% for equity funds. Some fund managers might be better than others, but track records alone may not provide enough insight to identify management skill. Stock and bond returns contain a lot of noise, and impressive track records may result from good luck. The assumption that strong past performance will continue often proves faulty, potentially leaving many investors disappointed. Conclusion The results of this study suggest that investors are best served by relying on market prices. Investment methods based on a manager’s ability to outguess market prices have resulted in underperformance for the vast majority of mutual funds. Despite the evidence, many investors continue searching for winning mutual funds and look to past performance as the main criterion for evaluating a manager’s future potential. In their pursuit of returns, many investors surrender performance to high fees, high turnover, and other costs of owning the mutual funds. We believe the underperformance of most US mutual funds highlights an important investment principle: The capital markets do a good job of pricing securities, which intensifies a fund’s challenge to beat its benchmark and other market participants. When fund managers charge high fees and trade frequently, they must overcome high cost barriers as they try to outperform the market. Choosing a long-term winner involves more than seeking out funds with a successful track record, as past performance offers no guarantee of a successful investment outcome in the future. Moreover, looking at past performance is only one way to evaluate a manager. In the end, investors should consider other aspects of a mutual fund, such as underlying market philosophy, robustness in portfolio design, and attention to total costs, all of which are important to delivering a good investment experience and, ultimately, helping investors achieve their goals. Data Appendix

Equity Funds: The sample includes funds at the beginning of the 5-, 10-, and 15-year periods ending December 31, 2017. Survivors are funds that had returns for every month in the sample period. Winners are funds that survived and outperformed their respective Morningstar category index over the period. US-domiciled open-end mutual fund data is from Morningstar and Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) from the University of Chicago.. Fixed Income Funds: The sample includes funds at the beginning of the 5-, 10-, and 15-year periods ending December 31, 2017. Survivors are funds that had returns for every month in the sample period. Winners are funds that survived and outperformed their respective Morningstar category index over the period. US-domiciled open-end mutual fund data is from Morningstar and Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) from the University of Chicago. Past Performance and Future Results: At the end of each year, funds are sorted within their category based on their three-year total return. The tables show the percentage of funds in the top quartile (25%) of three-year performance that ranked in the top quartile of performance over the following three years. Example: For 2017, only 29% of equity funds were ranked in the top quartile of performance in their category in both the previous period (2012–2014) and subsequent period (2015–2017). US-domiciled open-end mutual fund data is from Morningstar and Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) from the University of Chicago. The Mutual Fund Landscape study is conducted by Dimensional Fund Advisors LP. US-domiciled open-end mutual fund data is from Morningstar and Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP) from the University of Chicago. Equity fund sample includes the Morningstar historical categories: Diversified Emerging Markets, Europe Stock, Foreign Large Blend, Foreign Large Growth, Foreign Large Value, Foreign Small/Mid Blend, Foreign Small/Mid Growth, Foreign Small/Mid Value, Japan Stock, Large Blend, Large Growth, Large Value, Mid-Cap Blend, Mid-Cap Growth, Mid-Cap Value, Miscellaneous Region, Pacific/Asia ex-Japan Stock, Small Blend, Small Growth, Small Value, and World Stock. For additional information regarding the Morningstar historical categories, please see “The Morningstar Category Classifications” at morningstardirect.morningstar.com/clientcomm/Morningstar_Categories_US_April_2016.pdf. Fixed income fund sample includes the Morningstar historical categories: Corporate Bond, High Yield Bond, Inflation-Protected Bond, Intermediate Government, Intermediate-Term Bond, Muni California Intermediate, Muni California Long, Muni Massachusetts, Muni Minnesota, Muni National Intermediate, Muni National Long, Muni National Short, Muni New Jersey, Muni New York Intermediate, Muni New York Long, Muni Ohio, Muni Pennsylvania, Muni Single State Intermediate, Muni Single State Long, Muni Single State Short, Short Government, Short-Term Bond, Ultrashort Bond, and World Bond. For additional information regarding the Morningstar historical categories, please see “The Morningstar Category Classifications” at morningstardirect.morningstar.com/clientcomm/Morningstar_Categories_US_April_2016.pdf. Index funds and fund-of-funds are excluded from the sample. Net assets for funds with multiple share classes or feeder funds are a sum of the individual share class total net assets. The return, expense ratio, and turnover for funds with multiple share classes are taken as the asset-weighted average of the individual share class observations. Fund share classes are aggregated at the strategy level using Morningstar FundID and CRSP portfolio number. Each fund is evaluated relative to the Morningstar benchmark assigned to the fund’s category at the start of the evaluation period. So, if, for example, a fund changes from Large Value to Large Growth during the evaluation period, then its return will still be compared to the Large Value category index. Surviving funds are those with return observations for every month of the sample period. Winner funds are those that survived and whose cumulative net return over the period exceeded that of their respective Morningstar category index. Loser funds are funds that did not survive the period or whose cumulative net return did not exceed their respective Morningstar category index. Index data provided by Bloomberg Barclays, MSCI, Russell, FTSE Fixed Income LLC, and S&P Dow Jones Indices. Bloomberg Barclays data provided by Bloomberg. MSCI data © MSCI 2018, all rights reserved. Frank Russell Company is the source and owner of the trademarks, service marks, and copyrights related to the Russell Indexes. FTSE fixed income indices © 2018 FTSE Fixed Income LLC, all rights reserved. S&P and Dow Jones data © 2018 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global. Indices are not available for direct investment. Their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with management of an actual portfolio. Mutual fund investment values will fluctuate, and shares, when redeemed, may be worth more or less than original cost. Diversification neither assures a profit nor guarantees against a loss in a declining market. There is no guarantee investment strategies will be successful. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. I get a lot of questions about income distribution during retirement. How much can I take? How should my assets be positioned? What types of assets produce the most income? Total return income planning is a holistic approach that takes into consideration your entire portfolio, focusing on the primary drivers of investment growth. The Determinants of Return Obviously, we want our investment to grow over time. The principal we contribute, either initially or periodically through the years serves as the basis for future growth. Return on investment is determined by the combination of interest received from fixed income instruments (bonds, cd’s, money market accounts), stock profit sharing (otherwise known as dividends) and lastly by the gains or appreciation in value. When the time comes to begin generating income from investments, a total return approach looks holistically at the entire picture to systematically deliver an ongoing income stream. Income Requirements First, it’s essential to determine how much income is required, a question that cannot be answered without financial planning/analysis. In one form or another, it begins with figuring out expenses and cost of living during retirement. Next, comes integrating any recurring income from social security, pensions, annuities, etc. The difference between those two numbers represents a basic estimate of the income replacement needed from other investments. The simplicity of this example should not understate the potentially significant impact of things like taxation, inflation, and other estate planning considerations. The next question: Can the principal value of my portfolio plus its future growth through interest, dividends and capital appreciation (i.e. total return) make up the difference? Answer: “It depends.” Total return income planning incorporates a future expected rate of return to a portfolio which is further defined as “all investment accounts and their overall allocation to equity/stock and fixed income/bonds.” Lots of considerations come into play such as the total value, the equity to fixed income ratio; risk/return characteristics etc. Behavior can also have an impact on returns. Therefore, none of these points matter if the portfolio doesn’t fit with the investor's risk tolerance. The Act of Creating Income To supplement the need for income, cash is made available on a periodic basis (usually monthly, quarterly, or annually), by placing trades in one or a variety of the accounts. Tax efficiency is often stressed when determining whether the funds come from Traditional IRA’s, 401(k)’s, Roth IRA’s, taxable Individual/Joint Brokerage accounts or a combination thereof. The process of creating an ongoing income stream continues by following the same steps to replenish the funds needed for living expenses. It’s important to remember that today’s money won’t buy the same amount of goods/services as it will 10 years from now. Therefore, funds not required for current living expenses are efficiently left to grow in order to satisfy future inflation-adjusted income needs. Conclusion Growth and income may be the two most ambiguous financial terms that get thrown around. Total return essentially represents the most holistic incorporation of both. It provides the flexibility for both tax efficient distribution and unforeseen income needs. It also presents the opportunity to reduce cost, as opposed to many accurately maligned investment products containing multiple layers of hard-to-find fees and expenses. All data is from sources believed to be reliable but cannot be guaranteed or warranted. This information is intended for educational purposes, and it is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any particular security, products, or services. No one should assume that any discussion or information contained in this material serves as a receipt of, or as a substitute for, personalized investment, tax or legal advice. Diversification does not eliminate the risk of market loss. Investment risks include loss of principal and fluctuating value. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. Indices are not available for direct investment; therefore, their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with the management of an actual portfolio.

Check out this outstanding video illustrating the dangers of paying too much attention to financial media pundits. This comes from our partners at DFA, a company as dedicated to research and empirical evidence as we are.

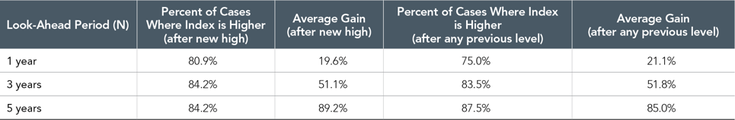

Throughout 2017, the S&P 500 Index recorded 62 new closing highs in 251 days of trading. In the first three weeks of January 2018 alone, the index crossed 10 new record closing highs in 13 days of trading. With stock indices continuing to set new highs, does this mean negative returns for stocks are on the horizon? When addressing this question, it is helpful to keep the following in mind: